1.1. Development of Lexicalism and the Lexical Integrity Principle

At its core, this paper is an exploration of the morphology-syntax interface, and the question of whether the combination of linguistic units into words and the combination of linguistic units into phrases should be treated as distinct grammatical components or, alternatively, as parts of a uniform grammatical system. Specifically, the present survey takes lexicalism – a theoretical position maintained by morphologists and syntacticians for over forty-eight years (outlined in Section 1.1 and 1.2) – as the lens through which to understand the nature of the morphology-syntax interface and the goals of grammatical theory in general. By considering the predictions made by present formulations of lexicalism (e.g. the Lexical Integrity Principle (Bresnan and Mchombo 1995)) regarding morphosyntactic interaction (Section 2), both cross-theoretically in Section 3 and cross-typologically in Section 4, it is shown that lexicalism does not properly characterize the morphology-syntax interface, and neither do linguistic theories based on lexicalist assumptions (Section 5).

Beginning in the 1950s with the advent of early Transformational Grammar, grammatical description was based solely on phonology and syntax; morphology, which at that time was not considered a field of study unto itself, was distributed across morphophonology (part of the phonological component) and syntax, which, in addition to phrasal combination, “[generates] the grammatical phoneme sequences of the language” (Chomsky 1957:32). The domain of morphology reemerged when Chomsky (1970) first attempted to constrain the power of grammatical (syntactic) theory by removing certain linguistic phenomena from the syntactic component and treating them instead in a separate lexical component (i.e., the lexicon itself) (Aronoff 1976:6)1.

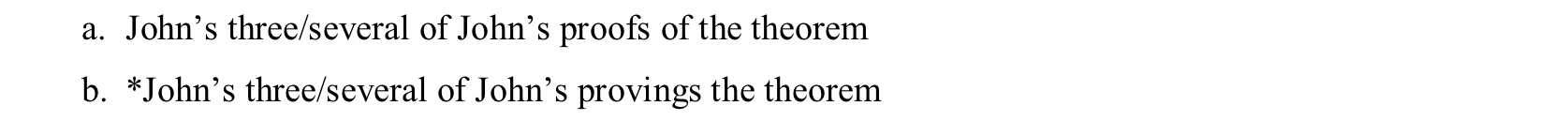

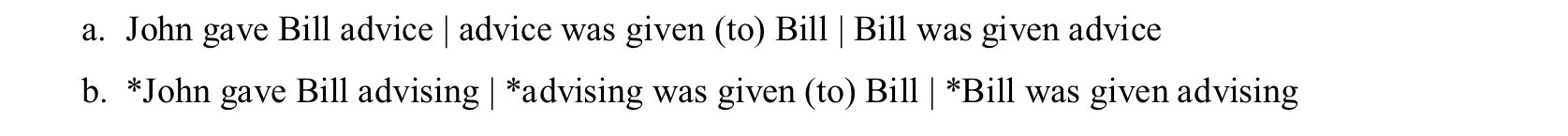

Chomsky (1970) suggests that derivationally complex and idiosyncratic information is present in, and the product of, an expanded lexicon, and is therefore separate from the syntax and immune to syntactic transformations. As evidence, Chomsky cites three differences between English derived nominals, which he views as fully derived prior to lexical insertion and any subsequent syntactic procedures, and gerundive nominals, which he claims are formed syntactically. For the sake of brevity, the present discussion will focus on one of the three2 points outlined by Chomsky; specifically, the structural behavior of derived nominals, as compared to that of gerundive nominals. Chomsky shows that the lexical category and internal structure of derived nominals is morphologically predetermined, allowing the derived nominal to participate freely in a range of syntactic configurations. This is in comparison to gerundive nominals, whose lexical category and combinatoric potential are syntactically determined, limiting their syntactic distributional properties. In particular, derived nominals are shown to have an NP internal structure (as determined by the lexicon) which allows them to be modified by a determiner or adjective in the syntax (Example 1a below), compared to the gerundive nominal in Example 1b which lacks this ability. Furthermore, the derived nominal is able to appear with the full range of determiners (Example 2a), while gerundive nominals cannot (Example 2b). This NP internal structure further allows derived nominals to appear freely in NP structures, where they can function as nominal arguments in, for example, active and passive ditransitive alternations (Example 3a compared to the gerundive nominal in 3b). Chomsky therefore concludes that certain word forms – in this case, the derived nominal – are fully derived prior to lexical insertion and any subsequent syntactic transformations, and are therefore the product of a separate, ordered lexical component.

Example 1

Example 2

Example 3

Chomsky’s (1970:188) proposal that “we might extend the base [syntactic] rules to accommodate the derived nominal directly”, which he terms the “lexicalist position”, as opposed to syntactically deriving the nominal (i.e. the “transformationalist position”), established morphology as an autonomous domain distinct from syntax. In order to enforce and restrict the separation between these two grammatical components, linguists have offered various interpretations of Chomsky’s original lexicalist position, two of which are provided below:

Interpretations of the Lexicalist Position

1. “[…] transformations do not perform derivational morphology.” (Jackendoff 1972:12-13)

2. “Syntactic rules cannot make reference to any aspect of the internal structure of a word.” (Scalise 1986:101)

The nature of the division between morphological and syntactic processes and the restriction on intramodular interaction imposed by the lexicalist position was further explicated and refined by Jackendoff (1972), Lapointe (1985[1980]), and Selkirk (1982), in what are referred to as the Extended Lexicalist Hypothesis, Generalized Lexicalist Hypothesis, and Word Structure Autonomy Condition, respectively.

Extended Lexicalist Hypothesis3

“[…] transformations cannot change [syntactic] node labels, and they cannot delete under identity or positive absolute exception. […] the only changes that transformations can make to lexical items is to add inflection affixes such as number, gender, case, person, and tense.” (Jackendoff 1972:13)

Generalized Lexicalist Hypothesis

“No syntactic rule may refer to elements of morphological structure.” (LaPointe 1985[1980]:8)

Word Structure Autonomy Condition

“No deletion or movement transformations may involve categories of both W[ord]-structure and S[entence]-structure.” (Selkirk 1982:70)

Di Sciullo and Williams (1987), in their Atomicity Thesis, emphasize the notion of accessibility of word-internal information, suggesting that not only is word-internal structure inaccessible to syntax but also that word-internal meaning components play no role in semantic composition at the phrasal level:

Atomicity Thesis

“Words are ‘atomic’ at the level of phrasal syntax and phrasal semantics. The words have ‘features’, or properties, but these features have no structure, and the relation of these features to the internal composition of the word cannot be relevant to syntax.” (Di Sciullo and Williams 1987:49)

As the status of morphology as an autonomous module of a language’s grammar remained the subject of debate throughout the late twentieth century, particularly as linguists explored the extent to which, and in what capacity, grammatical theory could be appropriately delimited and constrained, linguists took two divergent directions: on the one hand, in light of the apparent similarities between morphological and syntactic composition4, developing highly syntacticized models in which word formation processes are handled by the syntactic module itself, and on the other, developing lexicalist approaches to word formation, which supported the view that morphology is a largely independent system similar to phonology (Borer 1998:151). As a result, a lexicalist spectrum began to emerge, comprising a variety of approaches to word-internal structure and its relationship to or role in syntactic combination. On one end of the spectrum, all morphological composition is separate from syntax, and word-internal structure is completely invisible to syntactic processes; examples of these strong lexicalist hypotheses include the Atomicity Thesis of Di Sciullo and Williams (1987) above, as well as Anderson’s (1992) formulation below:

(Strong) Lexicalist Hypothesis

“The syntax neither manipulates nor has access to the internal form of words.” (Anderson 1992:84)

The other end of the spectrum constitutes approaches in which the independence of the morphological and syntactic components is still somewhat maintained, but syntax is in part responsible for morphological processes, or is permitted some degree of access to the internal composition of words. Examples of weak lexicalist hypotheses include Chomsky’s (1970) original lexicalist position, as well as the formulations of Anderson (1982:587) who assumes a split between inflection and derivation, declaring “inflectional morphology is what is relevant to syntax”, and Aronoff (1976), provided below5.

(Weak) Lexicalist Hypothesis

“[…] derivational morphology is never dealt with in the syntax, although inflection is, along with other such ‘morphological’ matters such as Do support, Affix Hopping, Clitic Rules, i.e. all of ‘grammatical morphology’.” (Aronoff 1976:8-9)

Borer (1998) notes that in both its strong and weak forms, lexicalism is enforced by maintaining a distinct lexicon and word formation component separate from syntax, and as a consequence, assumes an ordered relationship between each grammatical component. Borer therefore provides the following statement of lexicalism in terms of ordering, which is in turn closely related to the No Phrase Constraint of Botha (1981), also provided below.

Lexicalism in Terms of Ordering

“The [morphological] component and the syntax thus interact only in one fixed point. Such ordering entails the output of one system is the input to the other.” (Borer 1998:152-153)

No Phrase Constraint

“Morphologically complex words cannot be formed […] on the basis of syntactic phrases.” (Botha 1981:152-153)

Despite the apparent parallels (e.g. hierarchical structure) and particular points of contact (e.g. inflection) between morphology and phrasal syntax, there are clearly operations and categories unique to each component of the grammar. This has led linguists to maintain the fundamental generalization that restricts the interface between the internal structure of complex words and the rest of the grammar. The foregoing principles governing the relationship between morphological and syntactic processes are now commonly grouped together under a single rubric, the Lexical Integrity Principle. As articulated by Bresnan and Mchombo (1995), this principle concerns the distinctness of syntactic and lexical composition:

Lexical Integrity Principle

“A fundamental generalization that morphologists have traditionally maintained is the lexical integrity principle, which states that words are built out of different structural elements and by different principles of composition than syntactic phrases. Specifically, the morphological constituents of words are lexical and sublexical categories – stems and affixes – while the syntactic constituents of phrases have words as the minimal, unanalyzable units; and syntactic ordering principles do not apply to morphemic structure.” (Bresnan and Mchombo 1995:181)

The general notion of lexicalism6 and the Lexical Integrity Principle (which will henceforth be referred to as Lexical Integrity (LI)) is therefore a modular conceptualization of morphology and syntax, with the former functioning as the input to the latter, which arose from the historical need for separation between the syntactic system and certain morphological properties, and which was developed through a series of attempts to constrain the types and degrees of interaction between those components.

Section 1.1 Footnotes

1: Aronoff (1976:5-6) observes earlier work in generative phonology likewise led to a reintroduction of morphology; specifically, Chomsky and Halle’s (1968) attempts to constrain the power of phonological theory revealed that various phenomena (e.g. rules of inflectional morphology) were beyond a formal phonological theory (i.e. part of morphology).

2: The other two points Chomsky (1970:188-189) discusses include: (i) the productivity of the transformational process that produces gerundive nominals, as opposed to the apparent restrictions on the formation of derived nominals, and (ii) the generality of the relation between each nominal and the associated proposition; namely that derived nominals tend to be semantically idiosyncratic, as compared to the semantics of gerundives.

3: Spencer (1991:72-73) further elaborates on Jackendoff’s (1972) Extended Lexicalist Hypothesis, noting “the content of [the Extended Lexicalist Hypothesis] is that transformations should only be permitted to operate on syntactic constituents and to insert or delete named entities (like propositions). This means that they can’t be used to insert, delete, permute or substitute parts of words [which] in turn means that they can’t be used in derivational morphology.”

4: These similarities include the pre-theoretical observation that both involve the combination of linguistic elements into meaningful constituents (words from morphemes, and phrases, clauses and sentences from words). Other similarities are theory-specific, such as the notion that words exhibit hierarchical structures containing heads and their projections (Williams 1981), subcategorization (Lieber 1980), recursion (Josefsson 1998) and incorporation and government (Baker 1985a, b) – all concepts traditionally employed in syntactic description.

5: It should be noted that the weak lexicalism of Aronoff (1976) and Anderson (1982) differ with respect to whether inflection is a syntactic operation (in the case of the former), and whether inflection is a phonological operation (in the case of the latter) (Scalise 1986:102).

6: Bruening (2018:2) notes an additional meaning to the term lexicalism, which involves theories with enriched lexical entries that perform important functions in the grammar. An example of such a lexicalist theory is Combinatory Categorial Grammar (CCG) (Steedman 2000)). The term lexicalism is also used in this connection by Kay, Sag, and Flickinger (2015) to describe a theory of idioms, in which phrasal idioms are not words-with-spaces, but rather the product of combinatorial constructions and particular lexical classes (specifically, idiom predicators).