4.2. Typological Survey Observations

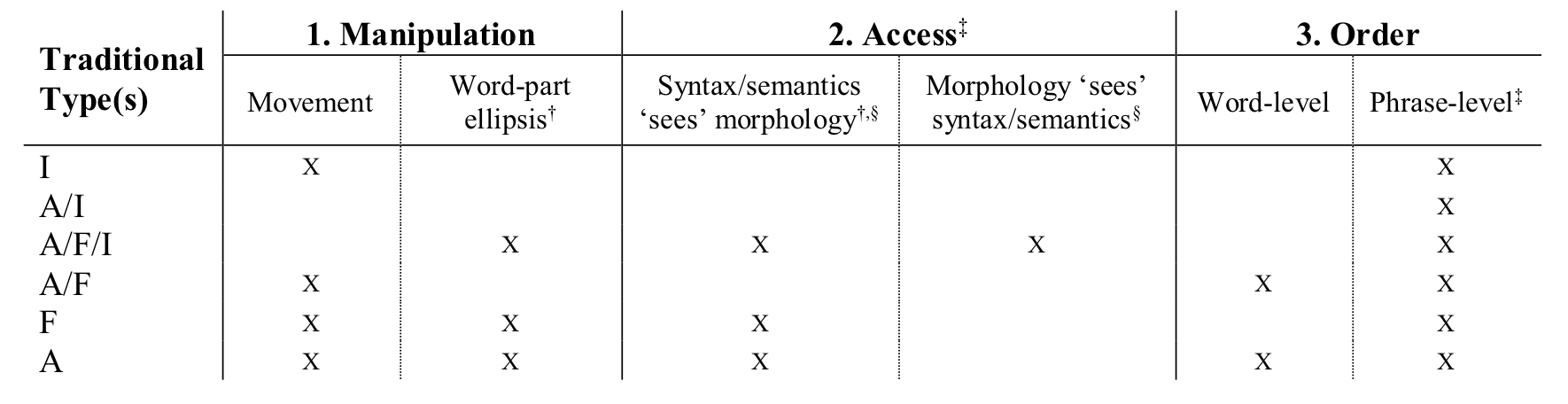

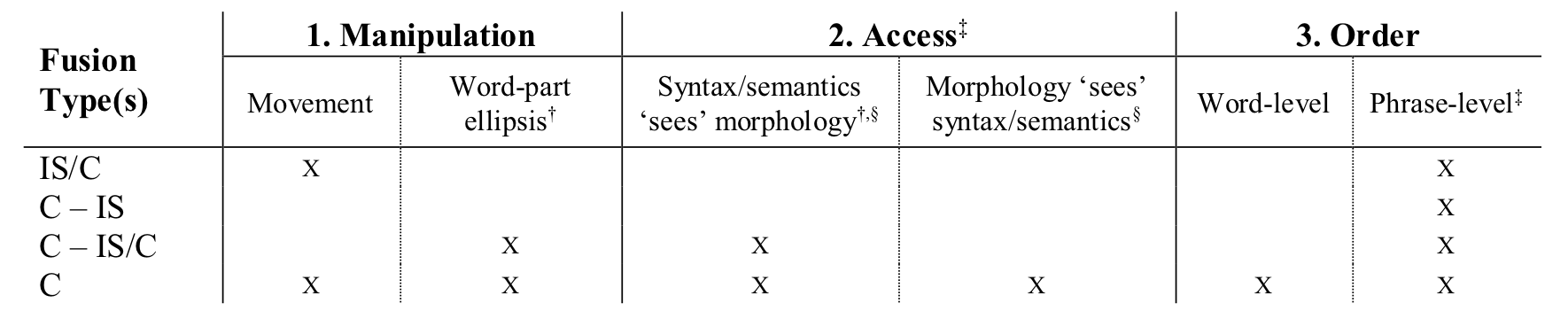

Adopting a similar methodology as that employed in the preceding theoretical survey (Section 3.2), specific manifestations of each LI violation are considered in terms of their general type(s) (MANIPULATION, ACCESS, and ORDER) along with their subtypes. In order to explore the cross-linguistic nature of LI and identify any potential correlations between individual violation types and specific morphological traits, the typological information provided in Table 2 in the prior section (and Appendix 7.3.1) is organized in relation to each LI violation (sub)type, presented below in Table 3 through Table 548. Phrase-level ORDER violations are the most cross-typologically present, occurring among all morphological types, while MANIPULATION violations (and its subtypes), which tend to occur among more synthetic languages, also manifest across a broad typological spectrum. For example, Table 3 and Table 4 show that phrase-level ORDER violations are attested among all typological profiles, whether characterized as AGGLUTINATIVE (A), FUSIONAL (F), and/or ISOLATING (I), or concatenative (C) and/or isolating (IS) phonological fusion.

Table 3 | Traditional Morphological Typology and LI Violation Types

Table 4 | Overall Type of Phonological Fusion and LI Violation Types

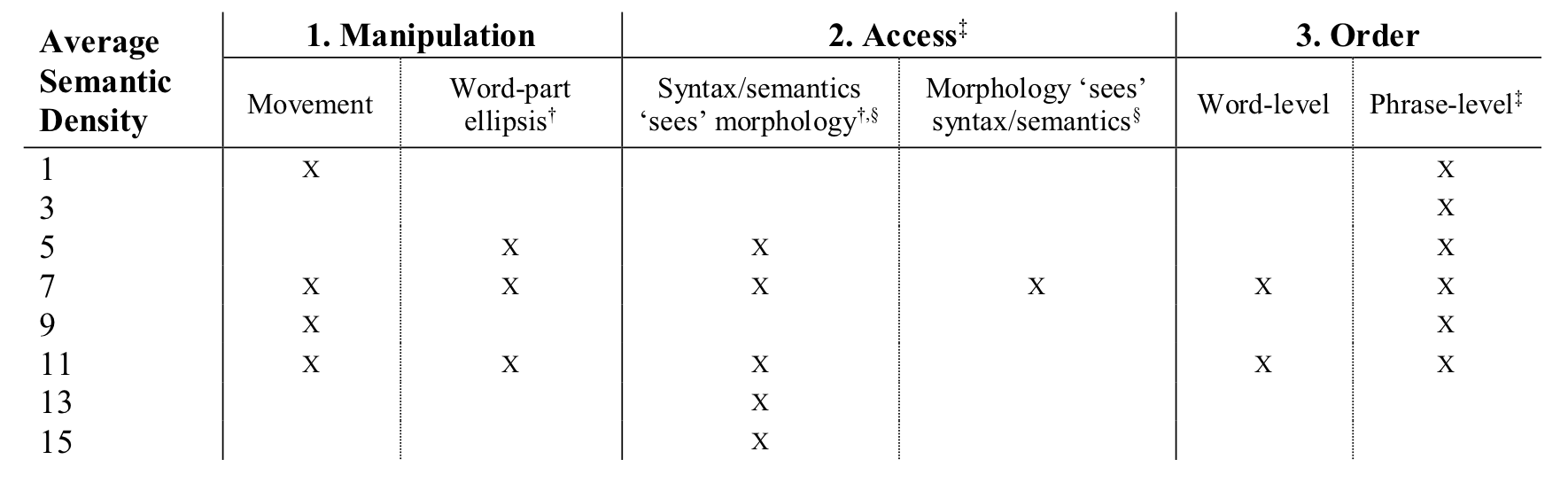

Furthermore, phrase-level violations are observed among all languages with low to relatively high measures of semantic density (Table 5), which also tends to correlate with the aforementioned synthetic morphological types, but not necessarily so49.

Table 5 | Average Degree of Semantic Density and LI Violation Types

MANIPULATION violations instead seem to associate more with synthetic properties (e.g. AGGLUTINATIVE/FUSIONAL and concatenative tendencies, cf. Table 3 and 4), and specifically mid-degrees of semantic density (cf. Table 5). The data point in the upper left corner comes from an apparent LI violation in Mandarin Chinese (Huang 1984:64) concerning the separability of verb-object compounds. Since compounding can be considered a type of word formation, and compounds typically function syntactically, semantically, and phonologically as indivisible words (Fabb 1998, Bauer 2009), the separability of these verb-object compounds could be conceived as a type of MANIPULATION (movement) violation. Adopting a diachronic perspective, compounding can also be viewed as a grammaticalization process resulting in derivational morphology (Hopper and Traugott 2003:40), in which case this particular example of compounding in Mandarin Chinese could be viewed as a slight shift toward synthetic properties, supporting a general connection between MANIPULATION violations and synthetic/concatenative properties. ACCESS violations (namely situations in which syntax/semantics ‘sees’ morphology) are similarly observed among the more synthetic typological systems (Table 3 and Table 4), however, in slight contrast with MANIPULATION violations, ACCESS violations tend to correlate with mid-to-high degrees of semantic density (Table 5).

Considering the general patterns above, I propose that specific interrelationships between each LI violation type and individual typological parameter provide the most intuitive connections between a given language’s typological profile, apparent violations of LI, and the nature of the morphology-syntax interface. Languages with low degrees of semantic density per grammatical marker and predominantly analytic (i.e. ISOLATING) morphology tend to exhibit syntactic methods for grammatical expression (e.g. word order and grammatical relations) and word formation (e.g. compounding). Since in some cases individual linguistic units may serve as function or content words in the syntax, or as derivational components in word formation (as in the case of Mandarin Chinese verb-object compounds noted above, English verb-particle constructions, and so on), it therefore stands to reason that languages with significant ISOLATING tendencies may appear to contain MANIPULATION violations (cf. the top row of Table 3, 4, and 5), where loosely bound linguistic forms such as clitics, preverbs, particles, etc., and potentially affixes, might appear to be syntactically manipulated.

Relatedly, languages with more analytic tendencies also exhibit phrase-level ORDER violations, where syntax appears to serve as the input to morphology. Given that such languages tend to rely on syntax (construed as the ‘input’ in the ordering relationship) for grammatical expression to a significantly greater degree than synthetic languages, it follows that the predominant system for grammatical expression would be extended into the traditional domain of word formation (e.g. productive phrasal compounding). Furthermore, since all languages exhibiting a phrase-level ORDER violation also demonstrate at least some degree of concatenative tendencies (cf. Table 4), situations of productive inflectional and derivational morphology appearing on phrases could be the result of specific morphological properties interacting with the fundamental role of syntax (analytic means of linguistic expression) cross-linguistically. Other cases of apparent phrase-level ORDER violations, such as words zero-derived from phrases, words derived from constructions, and potentially non-productive morphology on phrases, may simply be the result of lexicalization and grammaticalization processes, whereby phrases become words, and historically independent linguistic units, become affix-like.

Another noteworthy correlation is that between higher degrees of semantic density (Table 5), languages exhibiting synthetic morphology (the presence of concatenative, AGGLUTINATIVE, FUSIONAL traits (Table 3 and 4)), and ACCESS violations, where syntax/semantics ‘sees’ morphology. In contrast with prototypical analytic types, languages with higher degrees of semantic density per grammatical marker, and more synthetic typological profiles, tend to utilize morphological (e.g. affixation) and lexical means (e.g. suppletion) for expressing grammatical content. Considering that a highly semantically dense word form simultaneously expresses multiple semantic concepts, all of which may bear relevance to syntax, syntax and semantics would accordingly require ACCESS to specific (syntactically relevant, word-internal) information.

Mixed traditional typological profiles (middle of Table 3), exclusively concatenative phonological fusion (Table 4), and mid-ranges of semantic density (notably, an approximate degree of seven) (Table 5), correlate with the widest spectrum of LI violation types. While the measure of semantic density likely underscores each MANIPULATION, ACCESS, and ORDER violation for reasons noted above, each can be further associated with specific typological trends present in the mixed profiles. Certain MANIPULATION and ACCESS violations seem related to the presence of concatenative morphological processes and some sort of AGGLUTINATIVE and/or FUSIONAL (synthetic) properties, in coordination with mid-degrees of semantic density. Since such languages tend to form words in terms of linear sequences of bound morphemes, and each morpheme and/or word might encode multiple semantic concepts, apparent instances of syntactic MANIPULATION (e.g. word-part ellipsis) and ACCESS (e.g. syntax/semantics ‘sees’ morphology, and vice versa) may be observed. ORDER violations are correlated with specific analytic and synthetic tendencies within each (mixed) typological profile, with word-level ORDER violations most closely related to strictly synthetic word-formation (Table 3 and 4). In these cases, because grammatical markers are typically manifested as segmentable, linear sequences that are oftentimes bound to their host, morpheme orders that contradict the received predictions of TYPE (2) LINEAR MODELS (which assume morphophonological and morphosyntactic isomorphism (Borer 1998:170-171)) can be taken as ORDER violations on the word-level. On the other hand, phrase-level violations among these languages likely arise from an interplay of language-specific synthetic properties with co-present analytic traits, as discussed above50.

Specific LI violations are thus connected to particular, interrelated typological properties within and across languages. Furthermore, it is likely that the various violations observed across each language and associated typological profile are a result of that language’s particular state of diachronic change, and the role of morphology, syntax, and semantics therein. It goes without saying that languages are not simply static systems but also undergo change over historic time, as understood through various applications of the comparative method (Baldi 1990), and which is considered distinct from synchronic linguistic analysis (de Saussure 1983). Moreover, it has been observed that languages are in a constant “cycle of change” (Dixon 1994:182) among various typological profiles, and the complications these typological profiles (and attested violations) present for the morphology-syntax interface and LI demonstrate this. LI, and the theoretical assumptions that underlie it, are thus based on an ideal typological trait, particularly analytic tendencies toward syntactic expression. This is demonstrated by the few violation types manifested across highly ISOLATING languages, and the types that are observed likely arise from the effects of diachronic change (i.e. syntax more or less becoming morphology, and vice versa). The correlation between LI violations and synthetic morphology in general, and between each violation type and specific synthetic traits (i.e. high degrees of semantic density, concatenative phonological fusion, and mixed typological profiles), further show LI and its foundations lie in a syntactocentric view of grammar and the morphology-syntax interface, since the ACCESS of semantically dense words, MANIPULATION of complex word forms, and syntax-morphology ORDER violations present significant inherent challenges to theories based on such conceptualizations of grammar (namely, those which assume a robust, syntactic component to be distinct from, and subsequent to, morphology). Therefore, a proper grammatical theory of the morphology-syntax interface should be able to accommodate the diachronic effects on morphology and syntax, and more crucially model and describe the synchronic interaction between words and word-parts, phrases, and clauses, along with their meanings, regardless of a language’s typological characteristics.

Section 4.2 Footnotes

48: Table 3 through 5, in conjunction with Appendix 7.3.2 through 7.3.5, were consulted in order to identify the present observations. The more fine-grained analyses in each case (e.g. 7.3.2 through 7.3.5) support the observed patterns in the calculated averages (Table 3 through 5); therefore, only the average results are included in the present discussion. Furthermore, frequency of individual violation types is not taken into consideration since (i) the information was gathered from languages demonstrating at least some LI violations, and (ii) identifying clearly delineated classes of violation types is largely arbitrary (Section 1.2 and 2). Given the small sample size (only twenty-three individual languages are considered), it could be the case that the present observations are based on typological profiles that are disproportionately represented in the linguistic literature. Future work will ideally address such concerns.

49: For example, the English possessive pronoun their is monomorphemic (a low degree of synthesis, i.e. ISOLATING), but represents a higher degree of fusion, in that it singly expresses the semantic concepts ‘possession’, ‘topical referent’, ‘third person’, and ‘plural’ (a semantic density measure of at least four).

50: This could also be related to Jackendoff’s observations on linear concatenation of symbols (e.g. 2002:246-252), compounding (2010:423), and hierarchy of grammars (2014), in order to explain language acquisition, processing, emergence, evolution, etc.