3.1. Overview of Linguistic Theories

It has been observed that the divergence of current morphological and syntactic theories makes a comprehensive evaluation of LI challenging (Lieber and Scalise 2007:13), and the high degree of variation among implementations of LI across different grammatical frameworks only compounds this challenge (cf. Section 1.1). Moreover, a proper evaluation of LI is complicated by the fact that certain theoretical frameworks, occupying opposing ends of the lexicalist spectrum, are claimed to conform to LI, albeit at different levels of abstraction. For instance, strongly lexicalist theories can be said to conform to LI at the word level, since both derived and inflected word forms in such theories are the products of a separate morphological component, resulting from a distinct set of morphological rules and principles. These fully inflected and derived word forms are inserted into the syntax as is and are therefore opaque to any subsequent (strictly) syntactic operations. In contrast, weakly lexicalist theories are also claimed to conform to LI, but at the lexemic level (Harley 2015:1141), where a separate morphological component produces derivationally complete word forms (i.e. lexemes), which then receive inflection via syntactic and post-syntactic operations. By stipulating that the interaction of inflectional morphology and syntactic combination is necessarily the result of purely syntactic procedures (as per Anderson (1982:587)’s dictum “inflectional morphology is what is relevant to syntax”), one can craft a version of LI in which the interaction between inflectional morphology and syntax is permitted. In this sense, the uninflected word forms (lexemes) adhere to LI, since their internal, derivationally complex structure is invisible to syntactic operations, but at the same time they are available for syntactically conditioned inflectional affixation.

Therefore, given the inherent challenges of a complete, cross-theoretical evaluation of LI, several major linguistic theories are compared along three parameters – FRAMEWORK, MODEL OF GRAMMAR, and TYPE OF THEORY – in order to explore the relationship between LI and each major line of linguistic inquiry as comprehensively and precisely as possible, without becoming entrenched in the minutiae of theory-specific implementations of LI. FRAMEWORK is considered to be the mechanism used in describing syntactic (and potentially morphological) combination and semantic composition. The range of linguistic theories can be categorized as operating within either a UNIFICATION-BASED (NON-DERIVATIONAL)27 or DERIVATIONAL28 grammatical framework (Sag et al. 1986). In UNIFICATION-BASED frameworks, linguistic objects are modeled declaratively as feature structures29. A feature structure specifies (i.e. constrains) the possible combinations of phonological, syntactic, semantic, and contextual information used to characterize a given linguistic object. The building up of phrase-structural configurations, such as the combination of a VP with its subject NP, are modeled by the application of monotonic30 constraints of equality over various feature structures. These monotonic constraints specify how the information captured in each feature structure will be merged (through the formal operation of unification) with the result being a complete syntactic construction consisting of all (and only) the information present in that syntactic construction’s composite parts (Sag et al. 1986:238-243, Pollard and Sag 1987:7-8). Examples of linguistic theories with a UNIFICATION-BASED foundation include Generalized Phrase Structure Grammar (GSPG) (Gazdar et al. 1985), Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar (HPSG) (Pollard and Sag 1987, 1994), Lexical Functional Grammar (LFG) (Bresnan et al. 2016[2001]), Construction Grammar (CxG) (Fillmore 1988; Goldberg 1995, 2006; Michaelis 2012), and the Parallel Architecture (PA) (Jackendoff 1997, 2015).

DERIVATIONAL frameworks, by contrast, involve an underlying, fully specified D[eep]-structure, and a derived S[urface]-structure. D-structures are base-generated by the interaction of the lexicon and phrase structure rules, and represent the structural and thematic relations between sentential units. S-structures are derived from their relevant D-structures by the successive application of transformations (e.g. movement, deletion, etc.), according to principles of the grammar (Müller 2016:81-94). For DERIVATIONAL (or TRANSFORMATIONAL) frameworks31, this derivational relationship between D-structure and S-structure forms the basis of linguistic description and explanation (Sag et al. 1986:2), and for example provides an account of why the English active Muhammed hugged Li and passive Li was hugged by Muhammed have essentially the same meaning (i.e. they share a common D-structure). Examples of linguistic theories assuming a DERIVATIONAL framework include early Transformational Grammar (Chomsky 1957, 1965), Government and Binding Theory (GB)/The Principles and Parameters Approach (P&P) (Chomsky 1981, 1982), and the Minimalist Program (MP) (Chomsky 1995), as well as morphological theories that are couched within specific DERIVATIONAL frameworks, for example Lieber (1992) (with respect to GB/P&P), and Distributed Morphology (Halle and Marantz 1993) (with respect to Minimalism).

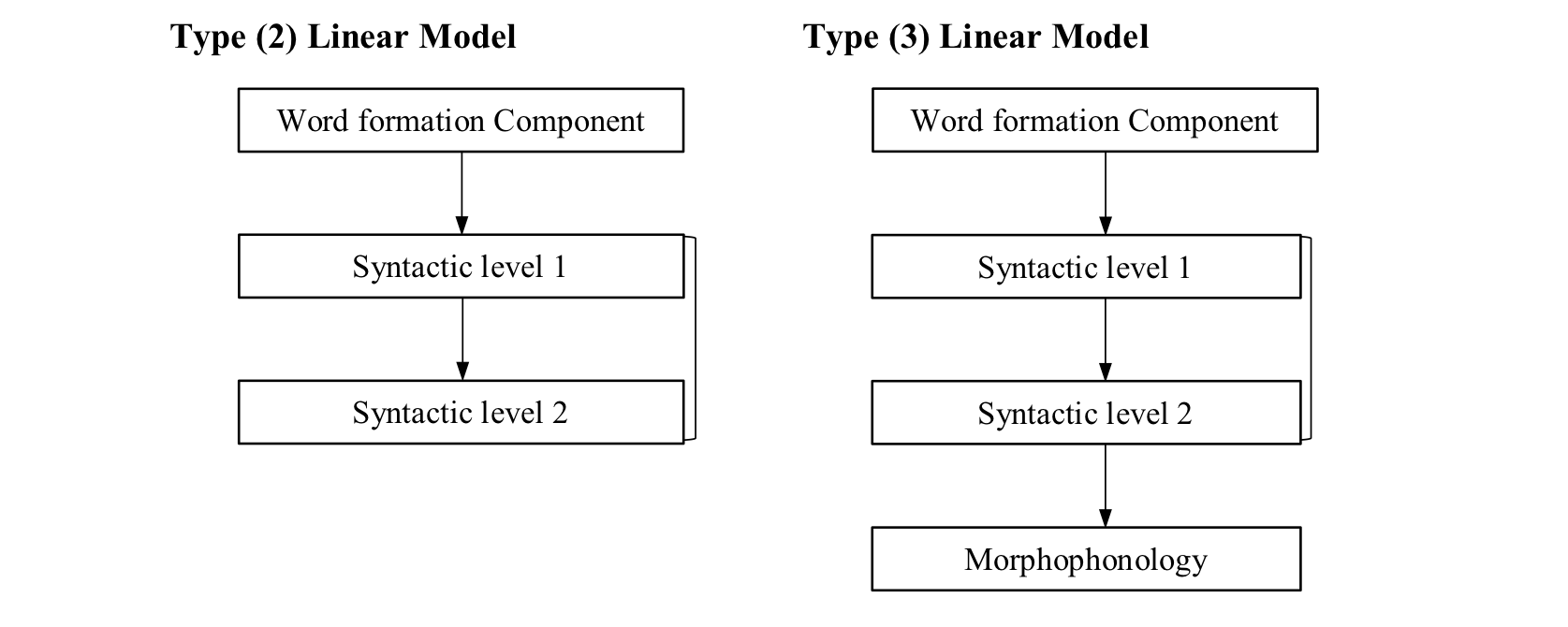

MODEL OF GRAMMAR refers to the overall architecture of the grammar, specifically whether a distinct lexicon, morphological, and syntactic component are assumed, and where word formation occurs with respect to syntax. In general, the various grammatical models are embedded within the two primary DERIVATIONAL and UNIFICATION-BASED linguistic frameworks, with DERIVATIONAL frameworks comprising types of LINEAR MODELS, as well as models which are FULLY SYNTACTIC, and UNIFICATION-BASED frameworks comprising UNIFIED and MODULAR (in correspondence) models. Within many DERIVATIONAL models, LI is enforced by ordering the morphology (comprising a lexicon and a word formation rule component) prior to the syntax, which “entails that the output of one [component] is the input to the other” (Borer 1998:152-153). This ordering of the morphological and syntactic components is reflected in two types of linear models: TYPE (2) LINEAR MODELS and TYPE (3) LINEAR MODELS (Borer 1998:153). In TYPE (2) LINEAR MODELS, the morphological component, which encompasses both derivational and inflectional processes, precedes D-structure and any syntactic operations, whereas in TYPE (3) LINEAR MODELS, the morphological component is separated from the component that phonologically realizes the morphophonology of words and word-parts. TYPE (3) LINEAR MODELS involve the introduction of categorial feature bundles prior to D-structure, and a separate post-syntactic morphophonological component provides phonology to the feature bundles generated by the lexicon and manipulated by the syntax. TYPE (2) and TYPE (3) LINEAR MODELS are represented below in Figure 2, demonstrating the general architecture of the grammar in terms of a series of ordered components.

Figure 2 | Linear Models (Borer 1998:153)

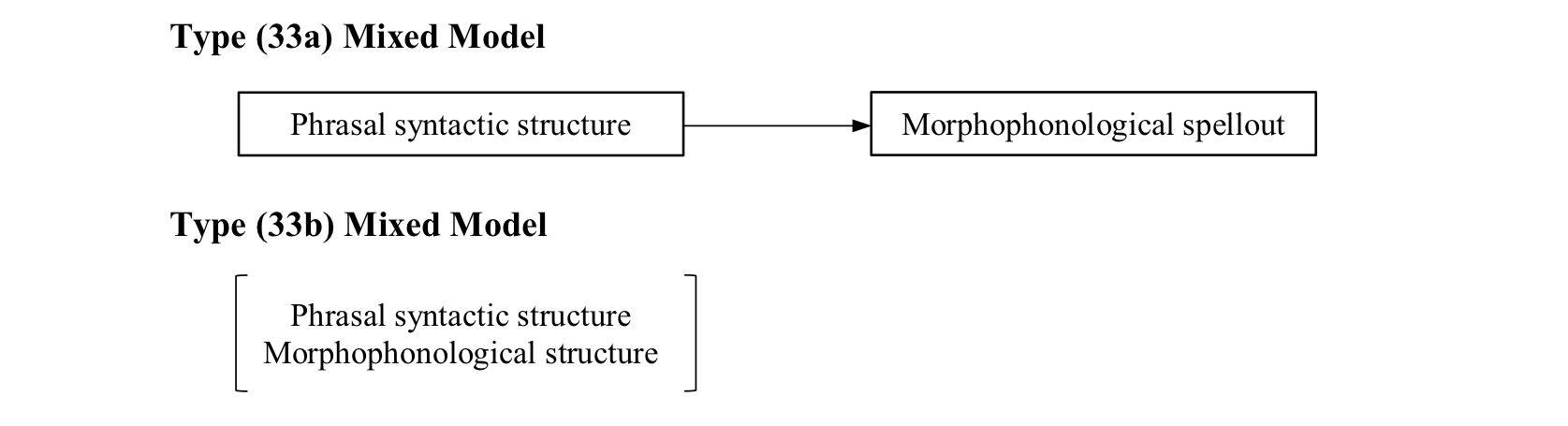

Similar to TYPE (2) and (3) LINEAR MODELS, and still within a DERIVATIONAL framework, are models which are FULLY SYNTACTIC. In contrast to the LINEAR MODELS outlined above, FULLY SYNTACTIC models eliminate a separate morphological component altogether, and instead treat word formation as obeying syntactic constraints and interacting with syntactic rules (Borer 1998:157). FULLY SYNTACTIC models can be further divided based on whether words are incrementally derived in the syntax, or realizationally spelled-out following the syntax. INCREMENTAL theories (Stump 2001:2) assume morphology is “information increasing”, in that the verb loves receives the meanings ‘third-person singular subject’, ‘present tense’, and ‘indicative mood’ by the concatenation of the root love and the suffix -s. For example, Lieber (1992) presents a FULLY SYNTACTIC INCREMENTAL account of word formation where affixes themselves, as well as roots and stems, are part of the lexicon and contain morphosyntactic features, which are then syntactically combined into complex morphological objects in tandem with phrasal combination (Harley 2015:1145). In contrast, REALIZATIONAL theories (Anderson 1992:12, Stump 2001:1) are so-called in that morpholexical rules and features ‘realize’ a given word’s morphophonological structure and morphosyntactic distribution (Harley 2015:1144-1145). For example, in a REALIZATIONAL account the two English plural forms cats and oxen are equivalently realized by virtue of the feature [+plural] (i.e. a separate morphophonological component produces the appropriate inflected forms for cat[+plural] and ox[+plural]) as opposed to an INCREMENTAL account, which would need to specify that the stem cat takes the plural -s suffix and ox the plural -en suffix in order to produce the composite plural forms cats and oxen. FULLY SYNTACTIC REALIZATIONAL theories roughly correspond to what Borer (1998) terms a TYPE (33a) MIXED MODEL (represented below in Figure 3), where the word formation component is ‘mixed’ with the syntax – “the formation of amalgams of functional heads is a non-morphological task [i.e. is fully syntactic], and its output, in turn, feeds into an independent morphophonological component that is syntactically irrelevant” (pp. 180). A FULLY SYNTACTIC INCREMENTAL model would consist solely of a syntactic component that receives stems and roots, as well as affixes, from the lexicon, and assembles both morphologically complex words and syntactic constituents according to well-defined syntactic procedures.

Figure 3 | Mixed Models (Borer 1998:180)

In contrast to LINEAR and FULLY SYNTACTIC models are architectures that either maintain the modularity of a morphological and syntactic component but put them in correspondence with one another, or provide a unified model of grammar that essentially dissolves the boundaries between a distinct morphological component and syntax completely. Grammatical architectures that maintain the modularity of morphology and syntax, but eliminate the linear ordering of these components, are what Borer (1998:180) refers to as TYPE (33b) MIXED MODELs (Figure 3), in which the morphophonological and syntactic components are placed in parallel, or in ‘correspondence’ (Harley 2015:1138). For instance, in LFG the syntactic component is composed of two structures: a f[unctional]-structure, which represents predicate-argument/grammatical relations, and a c[onstituent]-structure, which represents precedence and dominance relations in terms of classic phrase structure, and which takes fully inflected (and derived) word forms as its terminal nodes (Nordlinger and Sadler 2016:3-6). Morphology is therefore treated as a distinct component that forms the input to syntax (specifically c-structure trees). However, in contrast to LINEAR models, where morphology precedes (i.e. ‘feeds’) syntax, the parallel relationship between morphology and syntax in LFG has generally been handled in terms of competition between the morphological and syntactic components32. UNIFIED models, on the other hand, reject not only a linear relationship between morphology and syntax, but also the view that morphology and syntax comprise distinct modules at all. PA (and Relational Morphology (RM) therein) is one such theory: it sees the lexicon as structured by an inheritance hierarchy and extends this inheritance model to relations among phrasal types – a view that is shared by CxG and Booij’s (2007, 2010) Construction Morphology (CM) (Jackendoff and Audring 2016:469). In PA, a word and its possible affix(es) are ‘licensed’ or ‘motivated’ by the interface(s) between that word’s semantics (the meaning of the word and its part(s)), its morphosyntactic properties (the syntactic functionality of that word and possible affix(es)), and its phonological representation (how that word and potential affix(es) are produced). In this way, morphology is declaratively represented as an interface between phonology, syntax, and semantics, as opposed to being the product of an assembly procedure. Moreover, theories such as PA provide a UNIFIED linguistic model, in which language – from phonology and phonotactics to word formation to syntactic composition to semantic interpretation – is characterized as the result of simultaneous constraint satisfaction.

Finally, each theory is organized in terms of its overall ‘type’; specifically, whether it is a LEXICALIST or NON-LEXICALIST theory. As outlined in Section 1.1, lexicalism (and LI) has its origins in Chomsky’s (1970) proposal for a separation between lexical processes (e.g. derivation), comprising the lexical component of grammar, and syntactic processes, comprising the syntactic component. Therefore, in order for a theory to qualify as LEXICALIST, it must assume some degree of modularity (and autonomy) between morphology and syntax (Scalise 1986:20, Spencer 1991:72-73, Beard 1998:44, Toman 1998:306, Harley 2015:1138, Bruening 2018:1). The degree of separation between the morphological and syntactic modules is further represented by the ‘strength’ of lexicalism assumed by a given theory, or rather which processes (derivational and/or inflectional) are relegated to the lexical component or handled in the syntax. In general, STRONG LEXICALISM considers both derivation and inflection to be the result of a distinct morphological component, while WEAK LEXICALISM splits the two between the morphological and syntactic components, with derivation belonging to the former and inflection to the latter (Scalise 1986:101-102, Spencer 1991:178). In NON-LEXICALIST theories, morphology and syntax are not distinct modules; instead, with regard to SYNTACTICOCENTRIC theories, there is a single syntactic component that assembles both words and phrases, with words and word-parts (or abstract feature bundles, in the case of realizational models) able to occupy terminal nodes in the syntax (Harley 2015:1141). NON-LEXICALIST – UNIFIED theories, on the other hand, declaratively represent both morphological and syntactic processes as constructions (Goldberg 1995; Booij 2007, 2010) or schemas (Jackendoff and Audring 2016), making no distinction between separate grammatical components.

The taxonomy of linguistic theories in Figure 4 provides specific (groups of) approaches to morphology and syntax in relation to the theoretical assumptions that underlie them. Specifically, each line in Figure 4 represents a direct relationship between the overall FRAMEWORK (either UNIFICATION-BASED or DERIVATIONAL), and the theory type (NON-LEXICALIST, STRONG-LEXICALISM, and WEAK-LEXICALISM) and MODEL OF GRAMMAR33. Solid lines indicate a relationship between DERIVATIONAL frameworks and other levels of the taxonomy, while dashed lines indicate a relationship to UNIFICATION-BASED frameworks. The relation between each line and level of the taxonomy illustrates that, for example, theories that are generally understood to be distinct (e.g. HPSG and MP) are in fact similar in that both assume a type of STRONG LEXICALISM, but differ with respect to their overall FRAMEWORK and MODEL OF GRAMMAR (UNIFICATION-BASED and TYPE (33b) MIXED MODEL regarding HPSG, DERIVATIONAL and TYPE (2) LINEAR MODEL regarding MP). At the same time, the taxonomy shows that UNIFIED theories (e.g. RM, CxG) are maximally distinct from the work of Chomsky (1970), Aronoff (1976, 1994), and Anderson (1982, 1992).

Figure 4 | Taxonomy of Linguistic Theories

Section 3.1 Footnotes

27: Also referred to as INFORMATION-BASED or CONSTRAINT-BASED grammar formalisms (Pollard and Sag 1987, Shieber 1992), CORRESPONDENCE-TYPE (Harley 2015:1138-1139) and MODEL-THEORETIC approaches (Müller 2016).

28: Also referred to as GENERATIVE-ENUMERATIVE approaches (Müller 2016).

29: Feature structures are used to model different kinds of linguistic objects in different theories, and they are called different things: feature structures in HPSG (Pollard and Sag 1994:8), PATR-II (Shieber 1986:10) and SBCG (Sag 2007, Sag 2012, Michaelis 2012, f[unctional]-structures in LFG (Bresnan et al. 2016:44-48), feature categories or matrices in GPSG (Gazdar et al. 1985:20-27), among others.

30: See Sag et al. (1986:2-4) concerning the nature of monotonic constraints, compared to structure-changing derivational transformations.

31: While D-structure is no longer present in Minimalism (Chomsky 1995), it is still ‘derivational’ in that sentences are derived by the (external and internal) operation Merge (Müller 2016:124), or specifically, Syntactic Merge (cf. Lieber and Scalise 2007:21).

32: For example, Andrews (1990:519) “proposes [the Principle of Morphological Blocking] whereby the existence of a more highly specified form in the lexicon [e.g. a synthetic verb exhibiting subject agreement morphology] precludes the use of a less highly specified form [e.g. a corresponding syntactic phrase consisting of an unmarked verb form and a separate subject pronoun].”

33: The relationship between a given theory’s type of lexicalism and MODEL OF GRAMMAR is a close one, and given the state of the art in linguistic theory, that relationship can be considered in two ways: either one’s assumption regarding the type of lexicalism will constrain the model of grammar in which one operates, or the MODEL OF GRAMMAR one adopts will influence the type of lexicalism that is assumed. These two levels are kept distinct in the taxonomy in order to demonstrate, among other things, that despite the individual variation between grammatical models and associated theoretical approaches, each is related to a more general type of lexicalism.