1.2. LI Today and Its Challenges

While LI and its various formulations7 have traditionally been applied holistically to morphology and syntax, it has long been understood that LI subsumes two separable points, first noted by Postal (1969): some linguistic phenomena covered by LI involve (i) the relationship between syntax and the lexicon (e.g., situations of apparent non-local dependencies, in which the syntax may access the semantic, sublexical components of words), while others refer to (ii) the relationship between morphology and syntax (e.g., situations in which morphological processes affect phrasal syntax, or syntactic procedures affect word formation). Beginning in the 2000s, these two observations led some to question whether the constraints on the relationship between syntax and the lexicon, on the one hand, and the constraints on the relationship between syntax and morphology, on the other, are equally strong. Booij (2005, 2009) distinguishes two kinds of LI violations8: ‘accessibility’ violations and ‘manipulation’ violations. Booij claims that LI should allow for accessibility of word-internal structure to syntax and semantics, while disallowing manipulation, and suggests a revised version of LI:

Revised Lexical Integrity

“[…] syntax may need access to the internal structure of words […]. Hence the part of [LI] that forbids syntax to have access to word-internal structure appears to be incorrect.” (Booij 2005:14)

Lieber and Scalise (2007) do not discard components of LI but describe only what they consider to be “the strongest challenges to [LI]” (pp. 20), which they broadly categorize “according to the type of inter-component interaction that [those challenges] imply9” (ibid.): (a) morphology has access to syntax, (b) syntax has access to morphology, (c) morphology/semantics interactions, and (d) morphology/phonology interactions10. They argue for the following restatement of LI, referred to as the Principle of Limited Access, which acts in tandem with the formal morphological operation Morphological Merge to restrict (on a language-specific basis) the type and degree of morphosyntactic interaction.

Principle of Limited Access

“Morphological Merge can select on a language specific basis to merge with a phrasal/sentential unit; there is no Syntactic Merge below the word level.” (Lieber and Scalise 2007:21)

Morphological Merge

“Let there be items α, β, such that α is a base and β a base or affix. [Morphological Merge] takes α, β (order irrelevant) and yields structures of the form < α, β > γ, where γ is an X0, categorically equivalent to α or β, and α or β can be null.” (Lieber and Scalise 2007:21)

The Principle of Limited Access maintains LI by identifying distinct Syntactic and Morphological Merge operations, that can interface on language specific bases, and stipulating that the syntactic form of Merge does not operate below word level. Together with the Principle of Limited Access, Morphological Merge derives words, phrasal compounds, etc., (i.e. γ, functioning as a terminal node X0) according to language specific, abstract configurations of affixes, roots/stems, words, and/or phrases (i.e. α, β).

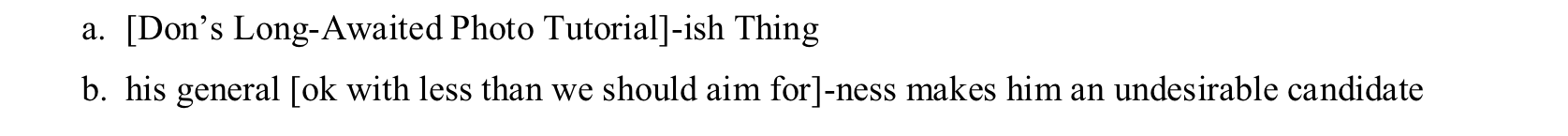

In line with Booij (2005, 2009) and Lieber and Scalise (2007), Bruening (2018) notes that LI disallows at least two separable types of linguistic phenomena: (1) cases where phrasal syntax can feed word formation (what he refers to as “Error 1” (pp. 2)), and (2) syntactic access of word-internal parts (referred to as “Error 2” (pp. 13)). Bruening shows that situations in which word formation takes fully formed syntactic phrases as input (i.e. syntax feeding word formation) conflict with a LI view that word formation and syntax are distinct, ordered components. For example, English permits phrasal derivations as below in Example 411, where the suffixes -ish and -ness attach to the fully-formed phrases (indicated in square brackets) Don’s Long-Awaited Photo Tutorial and ok with less than we should aim for, respectively.

Example 4

Additionally, situations in which syntax accesses word-internal elements conflict with LI, since word-internal structure is held to be opaque to syntactic relations, such as coreference. A transparent example of syntactic access of sublexical parts is found among so-called anaphoric islands (Postal 1969), in which a pronoun may be co-referential with a word-internal element elsewhere in the sentence. In Example 5 below, the pronouns him and he refer to the word-internal unit Reagan, located inside the derived word form Reagan-ite. Since coreference is traditionally understood as a syntactic relation (a binding relationship between NPs in a licit structural configuration), the cases in Example 5 would appear to be ones in which phrase-level grammar has access to word-internal parts.

Example 5

However, Bruening (pp. 15-23) goes further by postulating a third error type (“Error 3”), arguing that LI incorrectly predicts that morphology and syntax are truly separate components and obey different sets of principles; specifically, examples that are claimed to adhere to LI (e.g. extraction, coordination, and ellipsis) are shown to follow from LI-independent principles, such as the (theory-internal) distinction between phrases (XPs) and the terminal syntactic nodes (X0s) that may head them (pp. 24). Bruening demonstrates that certain processes are only able to affect phrases (namely extraction, coordination12, and specific types of ellipsis), while other processes that can be taken as violating LI affect only heads (e.g. ellipsis in certain coordinate structures, such as word-part ellipsis13 in half-brothers and (half)-sisters). Bruening therefore concludes that the predictions LI makes are both incorrect, since syntax has been shown to feed word formation and word-internal units can in fact be accessed by syntax, and do no explanatory work, since linguistic phenomena that appear to follow from LI can be accounted for through independent principles. In other words, no separable morphological component appears necessarily useful or essential to linguistic theory and explanation, leading Bruening to suggest a theory in which a single syntactic component is responsible for both words and phrases.

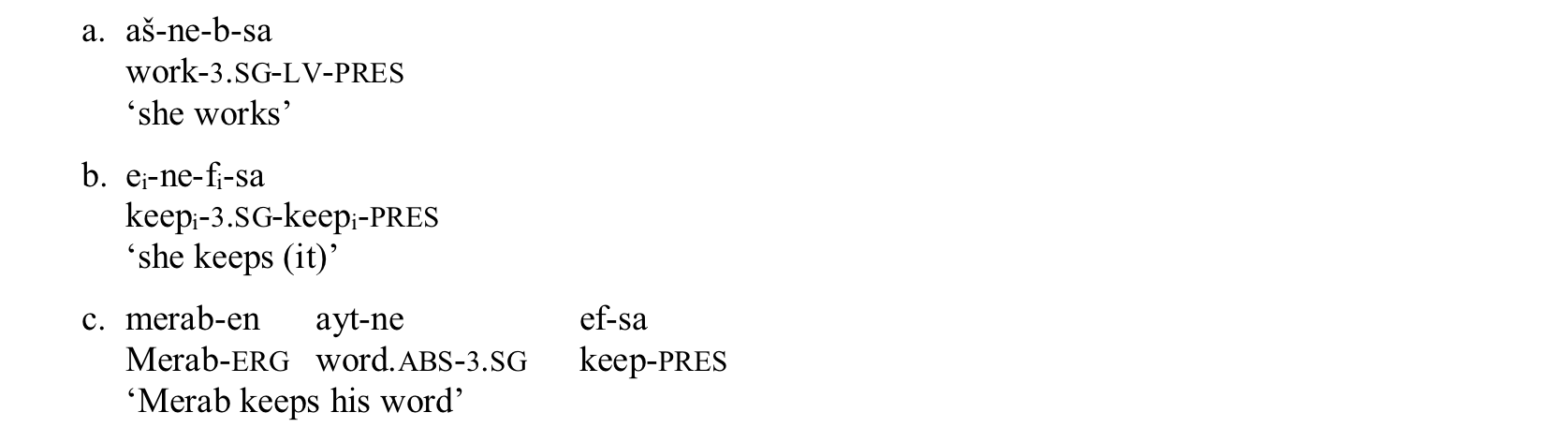

While it is clear that LI in its various incarnations is a significant underlying assumption in contemporary linguistic theory, the explanatory power and tenability of LI is poorly understood. Some claim it is essential, with morphology and syntax treated as distinct modules (e.g. Bresnan and Mchombo 1995, among others); some have claimed that, in light of the distinct linguistic phenomena that it covers, the principle must be maintained in certain cases and abandoned in other situations (e.g., Booij 2005, 2009; Lieber and Scalise 2007); and others argue that LI is unnecessary even when distinct classes of violations are recognized (e.g. Bruening 2018). Consequently, the relevance of LI to linguistic theory is nebulous, particularly since it is often simply not clear what linguistic phenomena LI is supposed to disallow, what constitutes a violation of LI, and why. For example, LI violations may manifest at the border of word formation and phrasal combination (e.g. the English phrasal derivations in Example 4 above), or as issues of interpretation rather than form, as in the case of anaphoric islands outlined above in Example 5. LI violations have also been observed in major morphosyntactic patterns, as in the positioning of person markers (also referred to as endoclitics) in Udi (Harris 2002). Udi person markers can occur as a suffix between other bound morphemes on a verb, as for example the third person singular marker -ne in Example 6a, but also morpheme-internally as in Example 6b, in which -ne- appears within the verb root ef ‘keep’. However, person markers also appear on words external to the verb, such as Example 6c where -ne is attached to the noun ait ‘word’, which functions syntactically as the direct object.

Example 6

Therefore, the placement of Udi person markers must be at least partially syntactic, since these markers can occur at the edge of an apparent VP, in much the same way that a clitic might (e.g. the ’s genitive ‘suffix’ in English, which can occur at the right edge of NPs, as in NP[the person on the street]’s opinion). It is then unclear what the proper analysis of an inflectional marker that sometimes behaves like an inflectional suffix and infix, and sometimes like a syntactic constituent, should look like, and whether it is in fact a violation of LI. Presenting a somewhat similar problem as the Udi data above, examples of coordination and ellipsis of word-parts, such as Example 7 below, can be analyzed in terms of a syntactic process whereby entire phrases are conjoined, followed by the deletion of word-parts (Chaves 2008) – in this case, a second pro in pro-choice and (pro)-gun control. If viewed from a strictly morphological viewpoint, the ellipsis of word-parts would constitute a syntactic manipulation of word structure and thus an LI violation.

Example 7

Conversely, the same phenomena can be viewed in terms of suspended affixation (Spencer 2005:83), where a single affix (pro- in the example above) has scope over two or more conjoined words (choice and gun), constituting an apparent morphological process and syntactic access violation at the phrase-level. Considerations such as the genesis and development of LI, its various (weak and strong) formulations, recent challenges and reformulations, and apparent violations, suggest that LI is a good lens through which to view the goals of linguistic theory and explanation in general, and the nature and efficacy of the syntax-morphology distinction specifically.

Section 1.2 Footnotes

7: There are other variants of lexicalism in addition to the ones presented and referenced in this paper; however, they all have in common some separation between a morphological and syntactic component.

8: LI violations are formally introduced and discussed in Section 2.

9: The types of inter-modular interaction identified by Lieber and Scalise (2007:20) are based on theory-internal considerations; specifically, strict divisions between various grammatical components. This is in contrast to, for example, construction-based analyses, in which all morphology would be an example of both morphology/semantics and morphology/phonology interaction, since morphological constructions exhibit a pairing between meaning and form. Constructional approaches are not directly amenable to Lieber and Scalise’s theory and methods, and consequent analysis.

10: Lieber and Scalise (2007:20-21) go on to state that inter-component interaction of types (a) morphology has access to syntax, and (b) syntax has access to morphology, are related to the morphology-syntax interface, and consider types (c) morphology/semantics interactions, and (d) morphology/phonology interactions, to be concerned with entirely distinct interfaces (the morphology-semantics interface and the morphology-phonology interface, respectively). Noting that the original formulation of LI is concerned only with the morphology-syntax interface, Lieber and Scalise therefore question whether any reformulation of LI should be concerned with examples of (c) and (d) at all, and the ultimate status of them in their argumentation is unclear.

11: Language data examples original to Lieber and Scalise (2007:9) (Example 4a) and Bruening (2018:6) (4b).

12: Bruening (2018:27-28) appears to consider all potential instances of X0 coordination to be phrasal coordination of fully projected XPs with ellipsis or right-node raising, supporting his analysis that coordination is a phrase-level process.

13: So-called word-part ellipsis, and how it can be reanalyzed in terms of suspended affixation, is further discussed below in Example 7, and similar cases in Section 2.