4.1. Dimensions of Morphological Typology

Drawing upon the typological classifications of individual languages provided by Bickel and Nichols (2013a, 2013b), and supplemented with (verified by) information from individual reference grammars (based on the author’s own search, the sources of which are provided in Appendix 7.4), the traditional morphological type(s)38, average semantic density39, and phonological fusion type(s)40 were determined for each language41 exhibiting at least one LI violation. Specifically, each language exhibiting at least one LI violation (as briefly discussed in Section 2 and listed in Appendix 7.2) was surveyed in terms of two approaches to morphological classification: (1) the traditional morphological types AGGLUTINATIVE, FUSIONAL, and ISOLATING (Comrie 1989[1981], Sapir 1921, etc.), and (2) degree of semantic density (or inflectional synthesis) and type of phonological fusion (Bickel and Nichols 2007, 2013a, 2013b). The latter approach is considered in addition to the former traditional scale since, as Bickel and Nichols (2013a, para. 1) observe, “such a scale conflates many different typological variables and incorrectly assumes that these parameters covary universally”. Therefore, both methods are employed in the event that a particular typological property, as potentially conflated by the traditional scale in (1), is relevant to the various LI violation types.

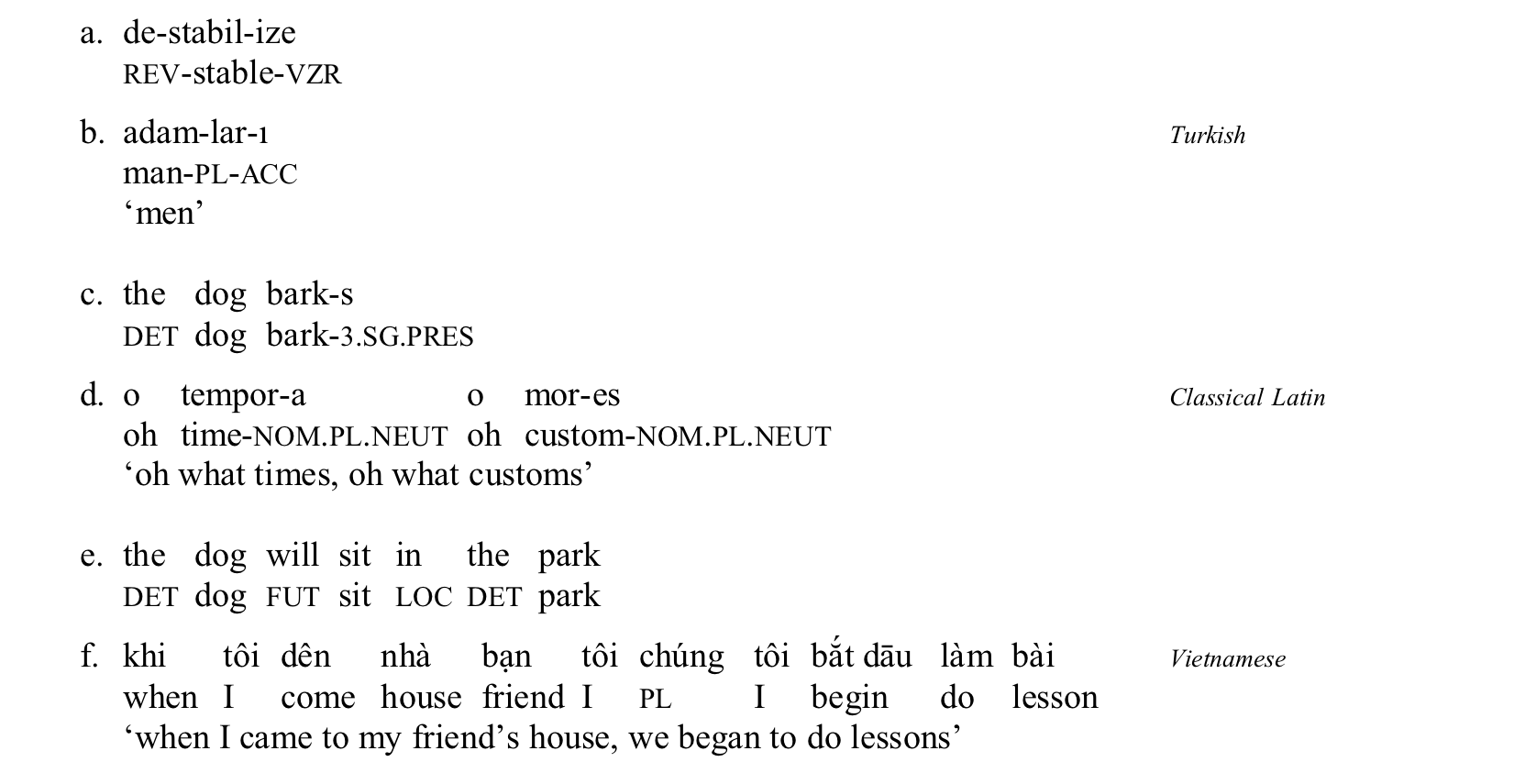

Traditional approaches to classifying the morphology of a given language include three prototypical categories (AGGLUTINATIVE, FUSIONAL, and ISOLATING), each of which are defined along two dimensions: degree of synthesis (i.e. the degree to which a language deviates from an ideal analytic type, or the amount of segmentable affixation a given language demonstrates), and degree of fusion (i.e. the degree to which a language deviates from prototypical agglutination, or the amount of grammatical information that is denoted by single, non-segmentable morphemes) (Comrie 1989:42-49). AGGLUTINATIVE languages are characterized by higher degrees of synthesis and low degrees of fusion, as demonstrated below in Example 15a and 15b; both the English verb destabilize and Turkish noun adamları are single words exhibiting higher degrees of synthesis (each is composed of three morphemes), and each morpheme and associated semantic category is easily segmentable (i.e. a low degree of fusion). On the other hand, FUSIONAL languages are defined in terms of (potentially) higher degrees of synthesis and higher degrees of fusion, as shown in Example 15c and 15d. While the Latin nouns tempora and mores in 15d are slightly synthetic (comprised of two morphemes), the suffixes -a and -es simultaneously encode the categories ‘plural number’, ‘accusative case’, and ‘neuter gender’. In contrast with the AGGLUTINATIVE, one-to-one relationship (and straightforward segmentation) of morphemes and semantic categories observed in Turkish (Example 15b, e.g. the individual expression of case and number), Latin exhibits FUSIONAL traits in that it deviates from such prototypical forms of agglutination. Similar FUSIONAL tendencies are present in the English verbal agreement ending -s, indicated in Example 15c. Finally, as opposed to the synthetic examples in 15a through 15d, the English and Vietnamese data in Example 15e and 15f represent canonical analytic forms in that each word form is monomorphemic (i.e. a low degree of synthesis) and associated with one semantic concept (i.e. a low degree of fusion), indicative of ISOLATING morphology.

Example 1542

Bickel and Nichols (2007) propose alternative means for describing morphological typology, whereby languages are not characterized along the traditional indices of synthesis and fusion, but rather according to typological parameters such as phonological fusion and semantic density43. Phonological fusion is defined as the degree to which grammatical markers44 are phonologically bound to their host (pp. 13), and can manifest as any one of the following three types:

-

Isolating – grammatical markers are single, free phonological words (isolating in this sense is therefore very similar to its traditional construal, e.g. Example 15e and 15f above).

-

Concatenative – grammatical markers are phonologically bound to their host word (under the present definition, concatenative includes patterns characteristic of both the AGGLUTINATIVE and FUSIONAL traditional morphological types, e.g. Example 15a through 15d above).

-

Non-concatenative – grammatical markers are added by means of modifying the host word, as opposed to the addition of segmentable, linear sequences of linguistic units45. Since this survey failed to identify languages exhibiting both an LI violation and productive non-concatenative morphology46, this specific type of phonological fusion is not considered in the overall typological survey.

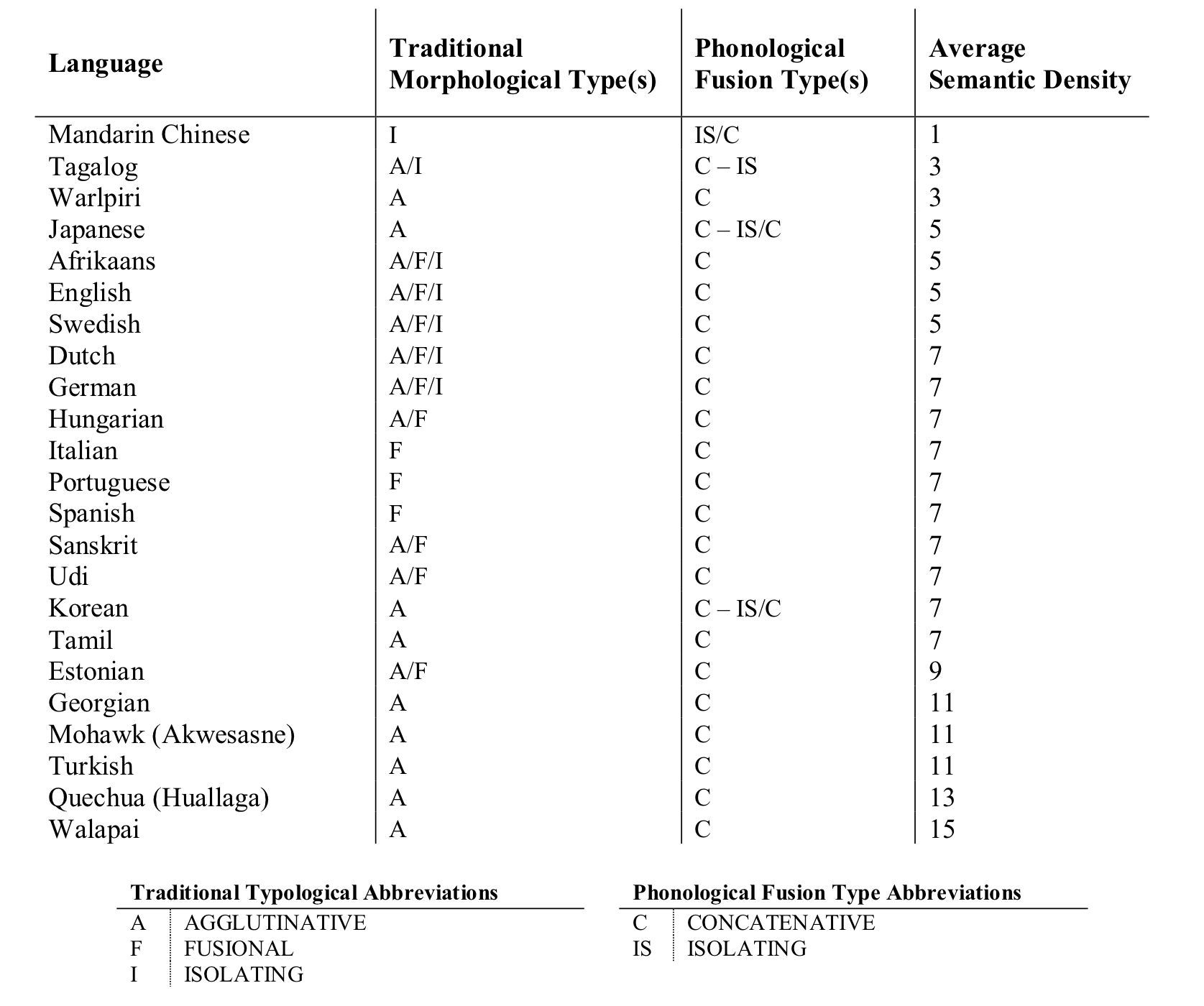

In addition to a language’s phonological fusion type, Bickel and Nichols (2007:21) identify two typological characteristics with respect to semantic density: exponence (density at the level of individual grammatical markers) and synthesis (density at the word-level). Exponence is a measure of the number of individual grammatical categories expressed by a single grammatical marker, which provides a more quantitative evaluation of the traditional notion of fusion, e.g. Example 15c and 15d above. Synthesis, which is also related to the traditional index of synthesis outlined above, measures “the number of [grammatical markers] and lexical roots that are bound together in one word” (pp. 22), ranging from ANALYTIC – SYNTHETIC – POLYSYNTHETIC. Given that the closely related traditional scale of ISOLATING – AGGLUTINATIVE – FUSIONAL is considered in this paper, under which polysynthesis may be considered a specific form of agglutination (or compounding), only exponence is reflected in the measure of semantic density. Furthermore, while semantic density is a measure of what is commonly considered to be inflectional grammatical categories, and LI violations involve both so-called inflectional and derivational properties47, it is included in the survey simply as a demonstration of how much semantic information a given word may morphologically or lexically encode for a specific language. Each language and corresponding typological classifications are provided in Table 2, in approximate ascending order of least to most synthetic.

Table 2 | Semantic Density and Morphological Types of Languages Exhibiting LI Violations

Section 4.1 Footnotes

38: In situations where a language demonstrates multiple (traditional) morphological types (e.g. English, as evidenced in Example 14a, 14c, and 14e below), each individual type is provided. Future work would address questions such as whether specific typological tendencies are associated with specific lexical domains (e.g. verbal, nominal, etc.) and whether the typological variation is generally derivational or inflectional in nature (assuming the SMH), and explore the potential relationship between the aforementioned considerations and LI violation types (and specific manifestations of each type), etc.

39: Average semantic density was calculated by first determining the individual inflectional semantic density of nouns and verbs in a particular language, and then deriving the average between the two measurements.

40: The overall phonological fusion type was identified in relation to the individual classifications of nouns and verbs. In the majority of cases, the fusion type between nouns and verbs matched, providing a straightforward categorization. In cases where verbal morphology (e.g. concatenative) is distinct from nominal morphology (e.g. isolating), both are noted as the overall type.

41: In a very limited number of cases, information for a genetically related language (typically within the same genus) if information for a particular language exhibiting an LI violation was not locatable.

42: Non-English data examples cited from Comrie (1989:43-44) (Vietnamese and Turkish) or primary source, Orationes in Catilinam 1.1 (Classical Latin).

43: Bickel and Nichols (2007:17) identify a third parameter – flexivity – which refers to the degree of variance, or allomorphy, of a particular grammatical marker in a specific language. For example, Latin demonstrates a higher degree of flexivity with respect to nominative case marking, as evidenced in the two Latin nominative endings -a and -es in Example 15d above. Since the present survey is concerned with the structural interaction of full morphological forms and syntax, and apparent syntactic/semantic access of specific morphological elements (i.e. the morphology-syntax interface), instances of phonological and paradigmatic variation (flexivity) are not considered.

44: Bickel and Nichols (2007:4) distinguish FORMATIVES (which generally correspond to bound morphemes) and WORDS (i.e. phonologically independent linguistic units). However, the more general term ‘grammatical marker’ will be used in place of FORMATIVE, in an attempt to avoid introducing additional terminology.

45: An example of productive, non-concatenative morphology includes the templatic (or root-and-template) morphology found among the Semitic (and certain other Afro-Asiatic) languages.

46: Following Bickel and Nichols (2013a)’s classifications of English and German, each are similarly considered as exhibiting predominantly concatenative means of morphological expression, despite ablaut (a non-concatenative process) also being present in these languages, although to a lesser degree.

47: This distinction assumes the Split Morphology Hypothesis (SMH) (Anderson 1982). See Booij (1993) for an argument against the SMH.