3.2. Theoretical Survey Observations

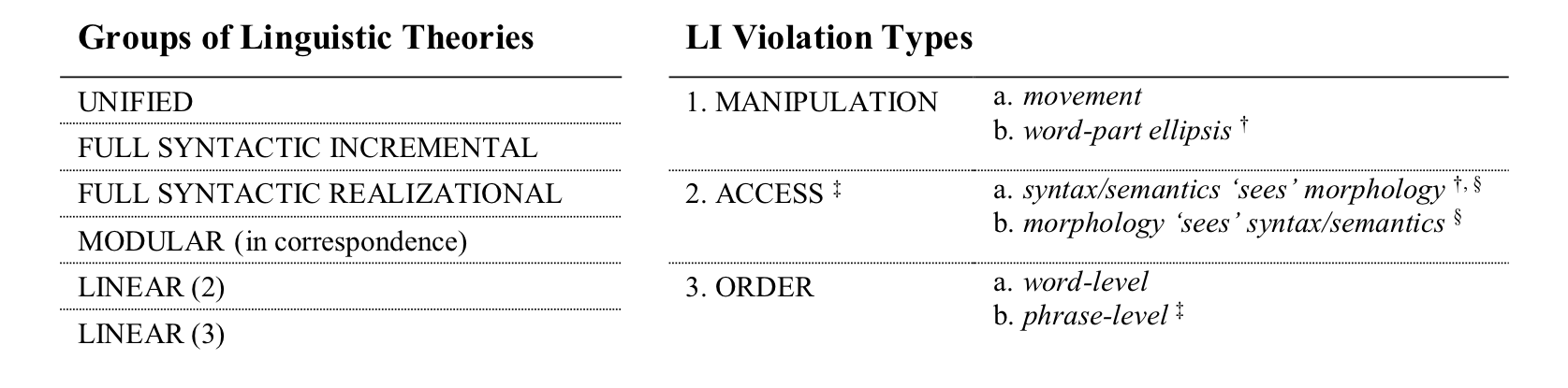

In order to address both the cross-theoretical nature of LI violations, as well as whether a particular type of violation is correlated with specific theoretical assumptions, individual implementations of each linguistic theory are considered generally with a specific focus instead on how each group of theories, and their inherited theoretical traits, relate to LI and its violations. The proceeding groups of linguistic theories (as outlined above Section 2, and provided toward the bottom of Figure 4) and LI violation types (Section 3.1, Figure 1) are compared:

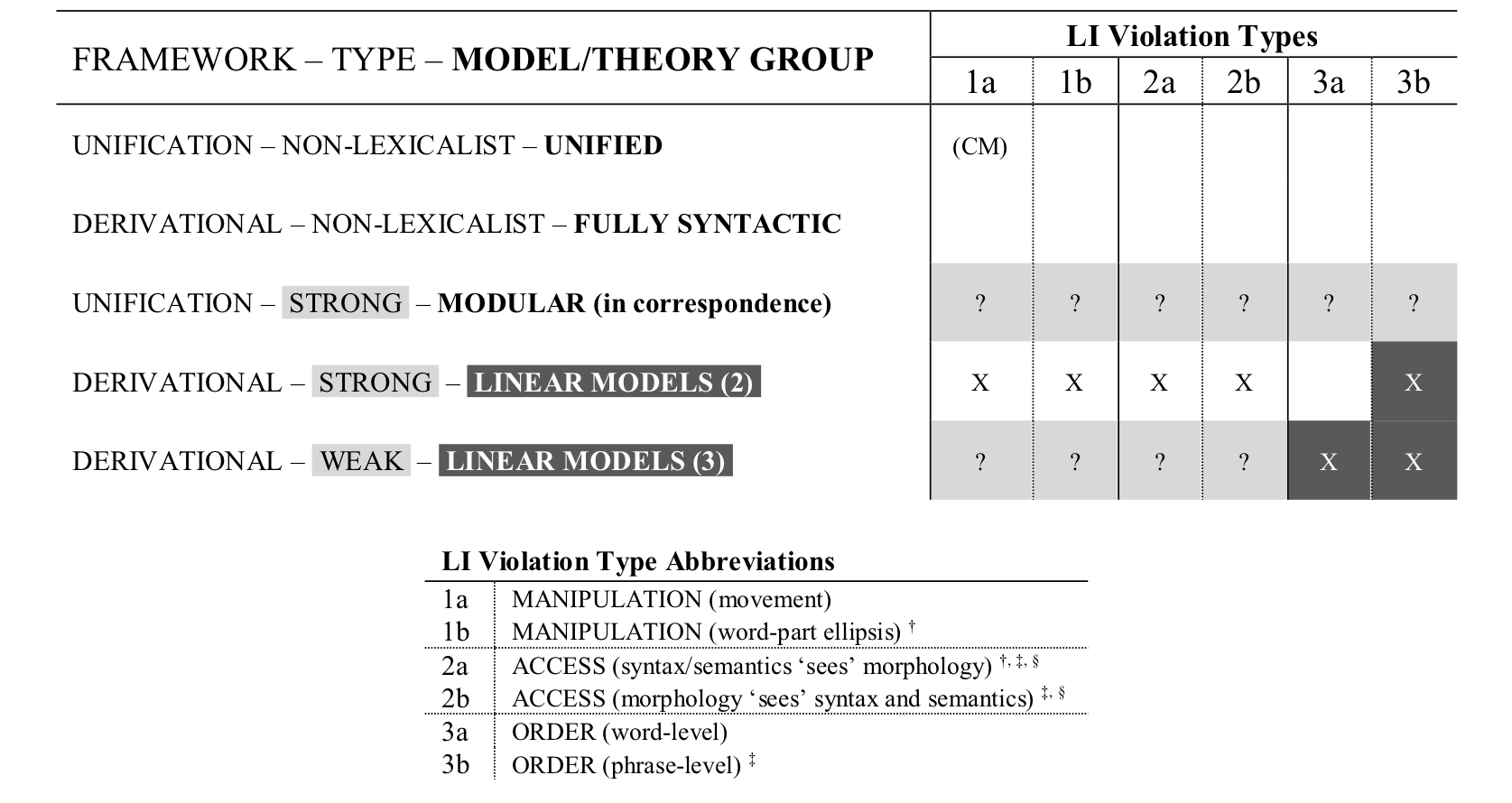

LI violations are entirely theoretically dependent, and as a result, exhibit no true cross-theoretical validity. However, it will be shown that specific types of violations are directly correlated with particular parameters of the linguistic theory one adopts. Table 1 provides a general comparison of each theoretical group (indicated in bold), in relation to the LI violation types (and subtypes) that the linguistic phenomena listed in Figure 1, Section 2 present for those theoretical approaches34. By considering each theory group in terms of its FRAMEWORK (UNIFICATION-BASED or DERIVATIONAL), lexicalist type (STRONG LEXICALISM, WEAK LEXICALISM, or NON-LEXICALIST), and MODEL OF GRAMMAR (TYPE (2) LINEAR MODELS, FULLY SYNTACTIC REALIZATIONAL, TYPE (33a) MIXED MODELS, etc.), in relation to each LI violation type, clear interrelationships emerge between specific properties each group of theories holds and the LI violations with which they contend.

Table 1 | Theoretical Parameters and LI Violation Types

ORDER violations, and both its subtypes, are specifically correlated with a given theory’s grammatical model (indicated in dark grey shading and white text in Table 1). TYPE (2) and (3) LINEAR MODELS, which position a word formation component as separate from and preceding syntax, are problematic for phrase-level LI violations since examples such as phrasal compounding, phrasal derivation, etc., contradict this ordering relationship. However, word-level ORDER violations are more closely associated with TYPE (3) as opposed to TYPE (2) LINEAR MODELS; given that TYPE (3) LINEAR MODELS integrate inflectional processes into the syntax, and word formation (i.e. derivation) precedes syntax, then instances in which the reverse order is observed violate this parameter. This is not the case for TYPE (2) LINEAR MODELS, since both derivational and inflectional affixation, independent of order, may be handled by separate word formation rules prior to syntax. Despite the ability of TYPE (2) LINEAR MODELS to treat apparent word-level LI violations, the fact that LINEAR (2) type theories assume both a TYPE (2) LINEAR MODEL and (forms of) STRONG LEXICALISM present several potential issues when considered in relation to the other violation types. Given the firewall imposed by STRONG LEXICALISM, in connection with the modular, linear architecture assumed by a TYPE (2) LINEAR MODEL (indicated within a solid black rectangle in Table 1), both MANIPULATION and ACCESS violation types (and their subtypes) should not be possible; particularly, syntactic operations should not MANIPULATE word-internal elements (whether via movement or word-part ellipsis) by virtue of the ordered, procedural nature of word formation with respect to syntax. Moreover, as a result of the barrier enforced by STRONG LEXICALISM, in coordination with the architecture of a TYPE (2) LINEAR MODEL, ACCESS of morphological structure by the syntax (and vice versa) (e.g. anaphoric islands, focus targeting sub-lexical units, construction dependent morphology, etc.) should be equally impossible. Therefore, LI violations present the most serious, inherent problems for LINEAR (2) type theories (e.g. Di Sciullo and Williams 1987, Chomsky 1995), in that nearly every violation type is not fundamentally amenable to these theoretical approaches.

The cross-theoretical permeation of the lexicalist spectrum (i.e. variable implementations of STRONG and WEAK LEXICALISM, indicated in light grey shading in Table 1) appears to be predominantly responsible for the broad potential for LI violations. These violations do not appear to necessarily correlate with the FRAMEWORK or MODEL OF GRAMMAR individually, but rather depend more on the linguist’s attitude toward LEXICALISM in relation to either parameter. For example, STRONGLY LEXICALIST – UNIFICATION-BASED theories maintain distinct morphological and syntactic components, however, given one’s opinion of what constitutes morphology and syntax proper, various linguistic phenomena can be principally integrated into one component over the other. And, considering the UNIFICATION-BASED nature of these STRONGLY LEXICALIST approaches, and the fact that the related grammatical model (TYPE (33b) MIXED MODEL) may position the morphological and syntactic components in a non-linear fashion (e.g. parallel, or in correspondence), what are then defined as distinct morphological and syntactic processes can interface more openly through unification and constraint satisfaction. Accordingly, MANIPULATION, ACCESS, and ORDER violations might indeed constitute violations, if one assumes a maximally strong conceptualizations of LI, morphology, syntax, as well as a TYPE (33b) MIXED MODEL as in LFG (e.g. Bresnan and Mchombo 1995)35; or they might not constitute violations, if certain linguistic phenomena are relegated to the lexicon/morphology and/or syntax (e.g. lexicalization of phrasal/derivational compounds, cliticization, suspended affixation, noun incorporation, etc., i.e. potential types of ORDER and MANIPULATION violations), which can then interface (i.e. ACCESS) more directly via unification. Likewise, MANIPULATION and ACCESS violations are variably problematic for WEAKLY-LEXICALIST – DERIVATIONAL theories for two reasons: first, certain processes may be deemed a morphological as opposed to syntactic procedure; and second, depending on one’s treatment of the pre-syntactic word formation and post-syntactic morphophonological components in the corresponding TYPE (3) LINEAR MODEL, ACCESS and MANIPULATION violations may be avoided by introducing abstract feature bundles in word formation, which are syntactically manipulated and accessed prior to morphophonological realization. LINEAR (3) type theories (e.g. Chomsky (1970), Anderson (1992), Aronoff (1994), etc.) are thus faced with serious challenges regarding ORDER (phrase-level) violations, due primarily to the particular MODEL OF GRAMMAR, while MANIPULATION and ACCESS violations may or may not be problematic, depending on theory-specific treatments of LI, morphology and syntax, and the grammatical architecture of TYPE (3) LINEAR MODELS. Similarly, MODULAR (in correspondence) type theories (e.g. LFG, HPSG, etc.) may be faced with MANIPULATION and ACCESS violations, due to the modularity of the grammatical model and the strength of LI assumed; however, such linguistic approaches may also accommodate each LI violation type, since (as noted) certain phenomena can be nested in either the morphological or syntactic component, and unification provides a higher degree of intermodular interaction.

Finally, those theories which essentially eliminate the LEXICALISM parameter (indicated within a dashed black rectangle in Table 1) are faced with little challenge when evaluated in terms of LI. Since each LI violation type involves some sort of morphosyntactic interaction, whether structurally or semantically, it follows that by removing the received barrier between each component, violations of the morphology-syntax interface turn out to be non-violations. In the case of UNIFIED theories (e.g. CM36, CxG, RM and PA, etc.), morphological and syntactic processes are declaratively represented in terms of constructions, or schemas, and relate and interface with one another via inheritance and relation. In slight contrast to UNIFIED approaches, which largely reject a formal distinction between morphology and syntax, since both are understood in terms of constructions (or schemas) (Goldberg 1995, Booij 2007, Jackendoff and Audring 2016), FULLY SYNTACTIC (INCREMENTAL and REALIZATIONAL) theories (e.g. Lieber 1992, DM, etc.) treat morphology as syntax, with syntactic rules responsible for both word and sentence formation. However, what UNIFIED and FULLY SYNTACTIC types of theories share is the elimination of a traditional morphology-syntax distinction, and consequently, the elimination of violations of that interface.

The present state of LI, as a culmination of its near fifty years of development and further redevelopment, is therefore manifest in at least two distinct theoretical parameters assumed within linguistic theory, and to varying extents: the degree and form of LEXICALISM imposed, and the architecture assumed by the MODEL OF GRAMMAR37. Also of note is that the FRAMEWORK (i.e. the general method used in describing the combination of morphological and syntactic units and their semantic composition) appears to bear little direct relation on the notion of LI and its violations, suggesting that either a UNIFICATION-BASED or a DERIVATIONAL approach can be equally descriptive, and possibly explanatory, depending on specific conceptualizations of LEXICALISM and the MODEL OF GRAMMAR.

Reflecting upon the present state of LI (Section 1.2), the empirical data and problems they pose to LI (i.e. violations, outlined in Section 2), and the theoretical sources of those problems, one straightforward conclusion at this point might be to remove the boundary between morphology and syntax, as in UNIFIED and FULLY SYNTACTIC types of theories, thereby eliminating both LEXICALISM as well as linear and modular architectures grammar. The question then becomes one of how best to treat morphology and syntax within a unified grammar (if conceived of separately), whether morphology and syntax form a single (unified) morphosyntactic system, or if morphology is truly just an extension of a single syntactic module. Any potential answer(s) to these questions will have profound ramifications for the descriptive and explanatory goals of the theory; these possibilities are briefly discussed in Section 5. However, given that each theory bases its approach to LI on parade phenomena in the exemplar language, the typological properties of those languages must also be considered. For example, word-level ORDER and ACCESS violations are generally unproblematic for highly morphologically isolating languages such as Mandarin Chinese, since such languages exhibit little to no sub-lexical structure that might phonologically manifest in unpredicted morphemic sequences on the one hand, and that would necessitate syntactic ACCESS of sub-lexical content on the other. Conversely, morphologically complex languages, such as Turkish and Mohawk, may certainly face word-level ORDER and ACCESS issues (and potentially MANIPULATION violations), since multiple derivational and/or inflectional affixes can attach to a single host. The relationship between LI and its theoretical assumptions, specific violation types, and the typological characteristics of the languages exhibiting those violation types, will now be explored in Section 4.

Section 3.2 Footnotes

34: There is a high degree of variability regarding each individual’s work. Accordingly, individual linguistic phenomena (within a given violation type) that may constitute a violation to one linguist may not to another, even when operating within the same theory. To reiterate, the present observations are therefore intended in a general manner, in order to illustrate the various interrelationships among LI and linguistic theory.

35: While STRONGLY LEXICALIST – UNIFICATION-BASED theories do not assume the procedural derivation of TYPE (2) and (3) LINEAR MODELS, the fact that “the interaction [between morphology and syntax] is still only one way” (Bruening 2018:2, f.n. 3) in such UNIFICATION-BASED approaches results in the potential for each LI violation type.

36: Apparent examples of MANIPULATION would remain violations in CM, since Booij (2009) leverages that point of LI in defining the notion ‘word’ (as noted in Section 2, f.n. 26), and further argues that “We need the prohibition on the movement of word constituents for explaining why in Dutch and German the rule of Verb Second that places finite forms of verbs in second position in root clauses cannot strand the prefix of a complex verb […], whereas the particle in particle verbs […] can be stranded” (pp. 86). However, given that CM assumes the framework of CxG (Booij 2013), it is not theoretically clear why Booij maintains a prohibition on syntactic movement as part of LI in general, and in his analysis of the Dutch and German Verb Second pattern and ‘stranding’ in particular. Specifically, CM would consider prefixed verb forms to be licensed by specific schemas (i.e. morphological constructions), while syntactically the particles in particle verbs would count as daughters in phrasal constructions. In other words, an entirely constructional approach renders maintaining a prohibition on the movement of word constituents unnecessary, since complex verbs and particle verbs can be fully characterized in terms of specific constructions, without appealing to particular properties of LI.

37: In some cases, it is likely that the MODEL OF GRAMMAR influenced the formulation of the type of LEXICALISM (e.g. Chomsky 1970), while in others, it is likely that LEXICALISM influenced the development, or refinement, of the MODEL OF GRAMMAR (e.g. Aronoff 1976, Anderson 1982). However, seeing that LEXICALISM is often taken as an implicit assumption that is inexorably interconnected to specific MODELS OF GRAMMAR (e.g. (TYPE (2) and (3) LINEAR MODELS, MODULAR (in correspondence)), determining the precise relationship between a theorist’s grammatical architecture and lexicalist assumptions (especially those theories that have been influenced by, but developed in reaction to, Transformational Grammar (Chomsky 1957, 1965, 1981, 1982) (such as GPSG, HPSG, LFG, etc.) is a quixotic enterprise.