2.1. Overview of LI Violation Types

It is important to first note that the analyst’s theoretical framework may determine what constitutes an LI violation, a point which is discussed in Section 3.2 and again in Section 5). Therefore, this section has two preliminary goals, which will serve as the foundational assumptions throughout the remainder of this paper: (i) a formal, working definition of LI will be provided, and (ii) a taxonomy of violation types is introduced, along with linguistic data examples demonstrating how the definition of LI in (i) facilitates the classification of distinct violation types.

Assuming a strongly lexicalist position in the spirit of Bresnan and Mchombo (1995:181) and Anderson (1992:84), in addition to the ordered modularity presupposed by LI (e.g. Botha 1981:18, Borer 1998:152-153), allows one to formulate certain predictions regarding the morphology-syntax interface. These predictions are presented below, and an attempt is made to relate each with the observations on LI of Postal (1969), Booij (2005, 2009), Lieber and Scalise (2007), and Bruening (2018)14:

Predictions Made by LI

-

Syntactic processes (e.g. movement, deletion, etc.) cannot affect a proper subpart of a word (cf. Postal’s point (ii), Booij’s ‘manipulation’, Lieber and Scalise’s category (a)).

-

Syntactic (and semantic) interpretation rules may not see a proper subpart of a word (e.g. anaphora, semantic scope, agreement between lexical units, etc.) (cf. Postal’s point (i), Booij’s ‘accessibility’, Lieber and Scalise’s categories (a) through (c), and Bruening’s Error 2).

-

The ordering of morphological processes relative to syntactic processes is unidirectional (e.g. morphological processes, such as derivational or inflectional affixation, conversion/zero derivation, etc.) cannot affect phrase-level constituents. In the case of weakly lexicalist approaches in which inflection, but not derivation, is determined by syntax, this predicts that inflectional markers should always occur external to derivational markers15 (Beard 1998:45-46) (cf. Bruening’s Error 1 and Lieber and Scalise’s category (a)).

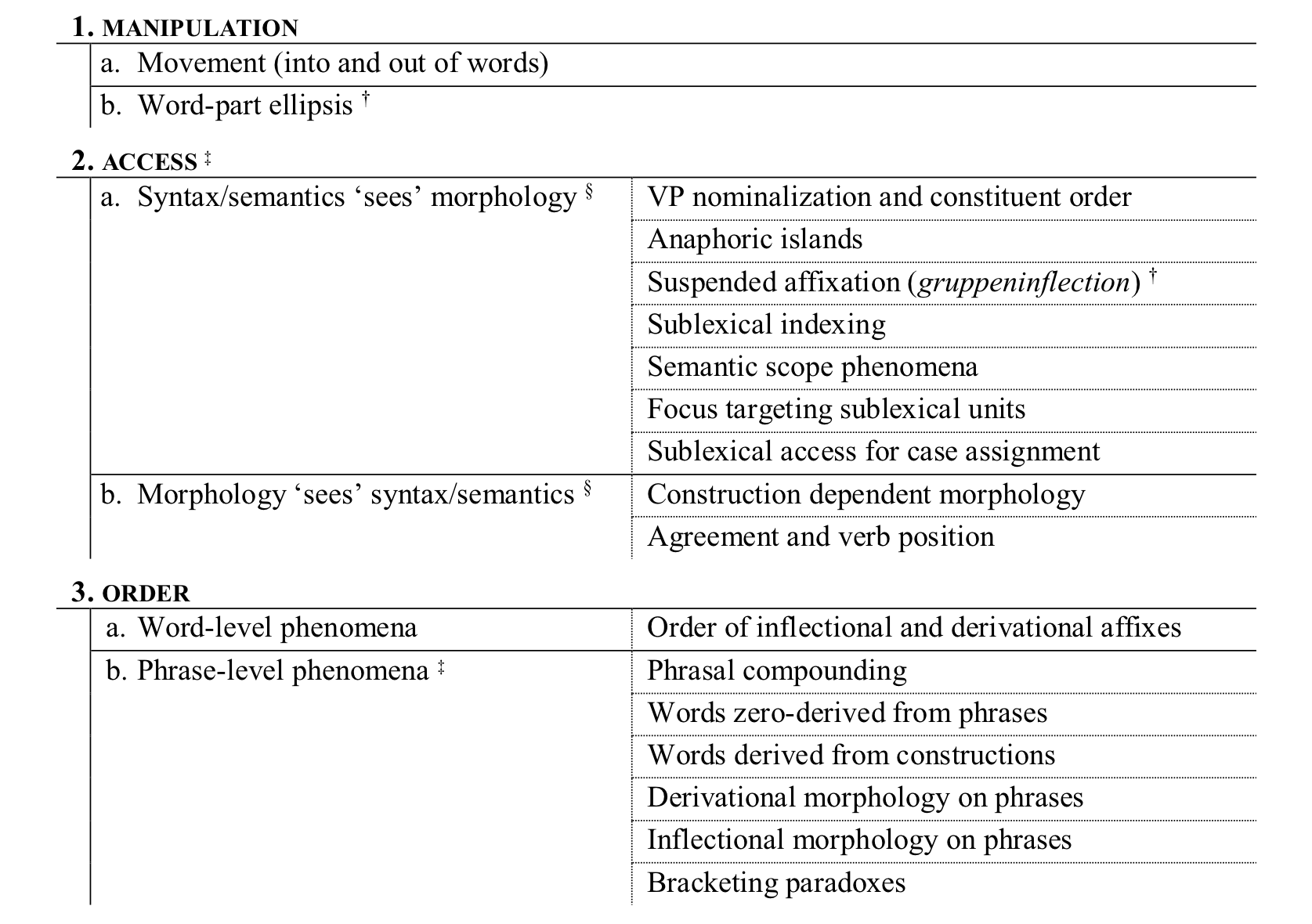

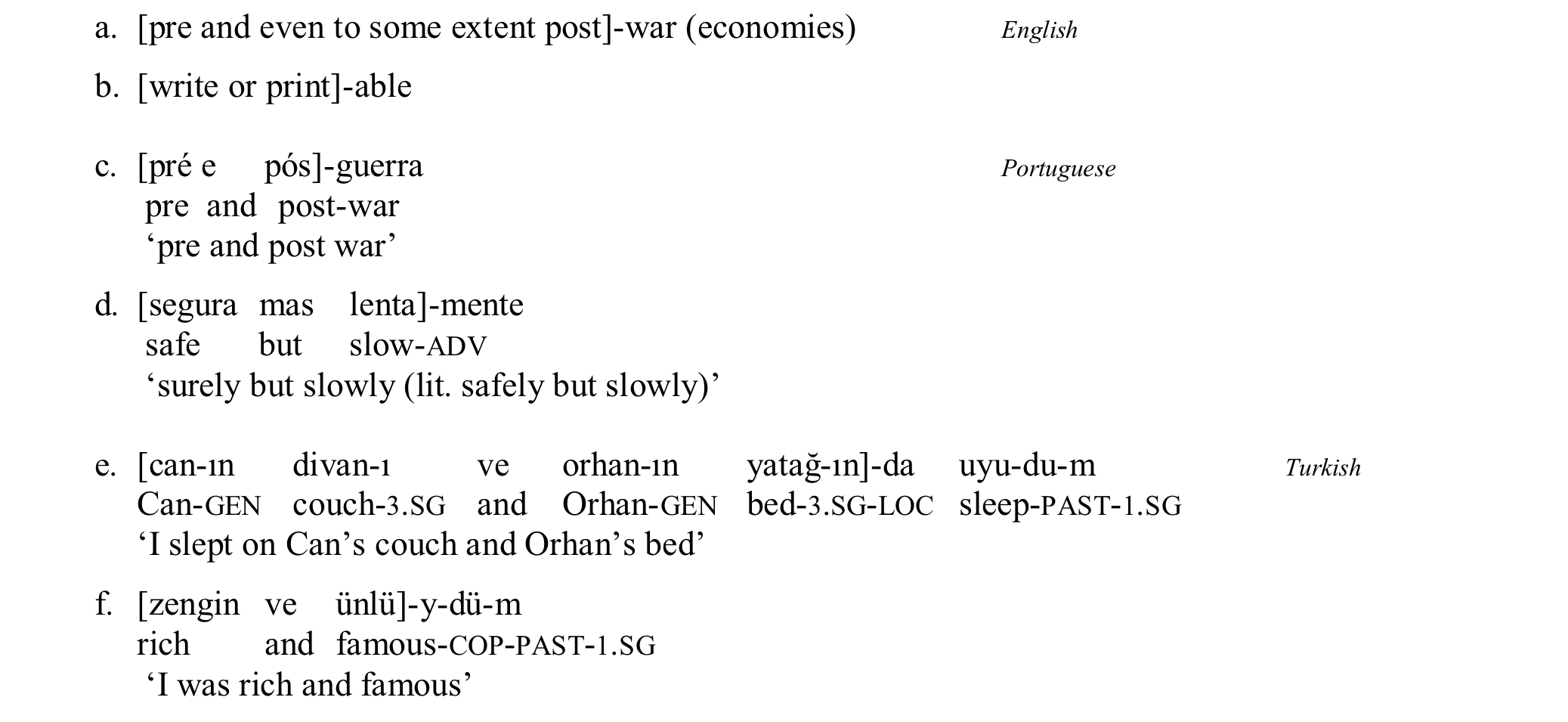

The predictions made by a strongly lexicalist, modular view of LI facilitates the development of a taxonomy of apparent LI violations, provided in Figure 116. Since LI is explicitly concerned with negative exceptions to the principle (i.e., those violations which it correctly precludes), only positive exceptions are considered as proper violations. Corresponding to each aforementioned prediction, three general violation types are identified: MANIPULATION violations, which involve syntactic processes that are typically assumed to operate on indivisible word forms (i.e. terminal nodes) and phrasal constituents; ACCESS violations, which involve bidirectional, intermodular interaction between morphology, syntax, and semantics; and ORDER violations, which involve situations where observable linguistic forms contradict the supposed linear order of morphology and syntax. In some, if not most, cases, specific violations and their overall types can be reanalyzed in terms of an opposing perspective, as noted above regarding word-part ellipsis/suspended affixation in Section 1.2, Example 7. These points of potential reanalysis are indicated in Figure 1 by means of the co-indexed superscript symbols †, ‡, and §17.

Figure 1 | Taxonomy of LI Violations Types

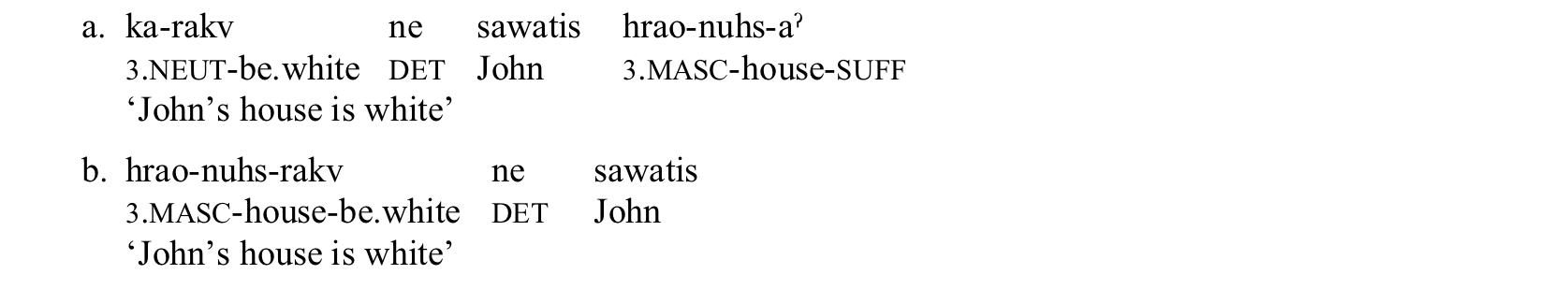

Furthermore, the general LI violation types MANIPULATION, ACCESS, and ORDER, each comprise at least two subtypes. For example, MANIPULATION may include instances of apparent syntactic movement into words, as in the example of Mohawk noun incorporation (Baker 1985a:38) in Example 8 below. Baker argues that the relationship between the sentences in 8a and 8b, which he syntactically represents by means of the respective phrase structure trees in Example 9a and 9b, is a derivational one, with 8a functioning as the input, and syntactic (head) movement of the lexical unit nuhs ‘house’ onto the verb root rakv ‘be white’ producing the observed output in 8b18. Therefore, instances of noun incorporation and the like (e.g. Udi person markers Example 6a-c in Section 1.2) are considered to be a specific subtype of MANIPULATION – particularly, movement (into and out of words).

Example 8

Example 9

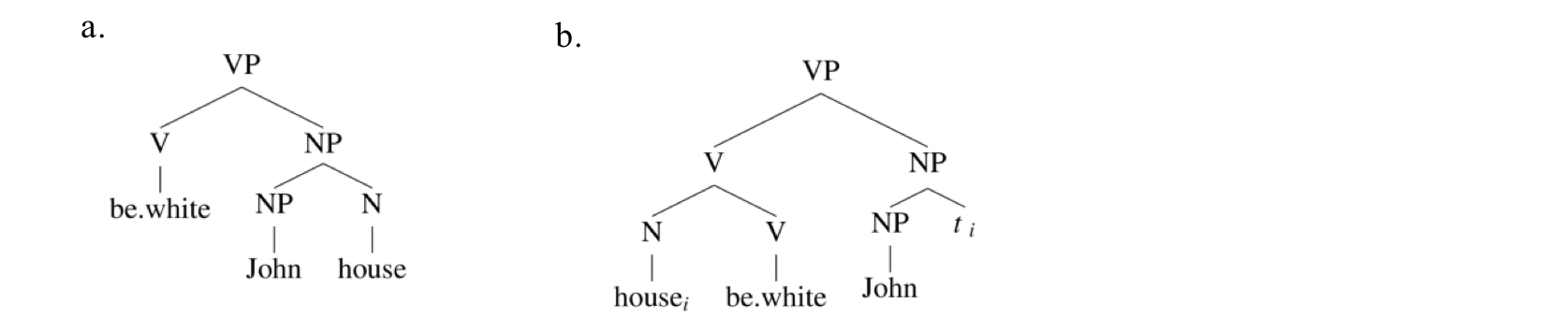

A second subtype of MANIPULATION includes linguistic phenomena which can be fully analyzed as either a syntactic or morphological process. As previously noted in Section 1.2 (Example 7), examples such as those presented below in Example 1019 can be characterized as a syntactic process of word-part ellipsis, where a particular morphological element is repeated across words, and subsequently deleted by the syntax. From a strictly morphological perspective, examples of coordination and deletion of word-parts then constitute a form of MANIPULATION violation, and it is necessary to distinguish a second subtype of MANIPULATION violations to include potential instances of word-part ellipsis. However, considering that word-part ellipsis readily yields to a morphological analysis in terms of suspended affixation, where, for example, the Portuguese adverbial ending -mente in 10d, and the Turkish locative suffix -da in 10e, take scope over the preceding conjoined adjectives ADJ[segura] mas ADJ[lenta] ‘safe but slow’ (10d) and NPs NP[canın divanı] ve NP[orhanın yatağın] ‘Can’s couch and Orhan’s bed’ (10e), examples of word-part ellipsis must also be recognized as a specific type of syntactic ACCESS violation, in which syntax/semantics accesses word-internal structure.

Example 10

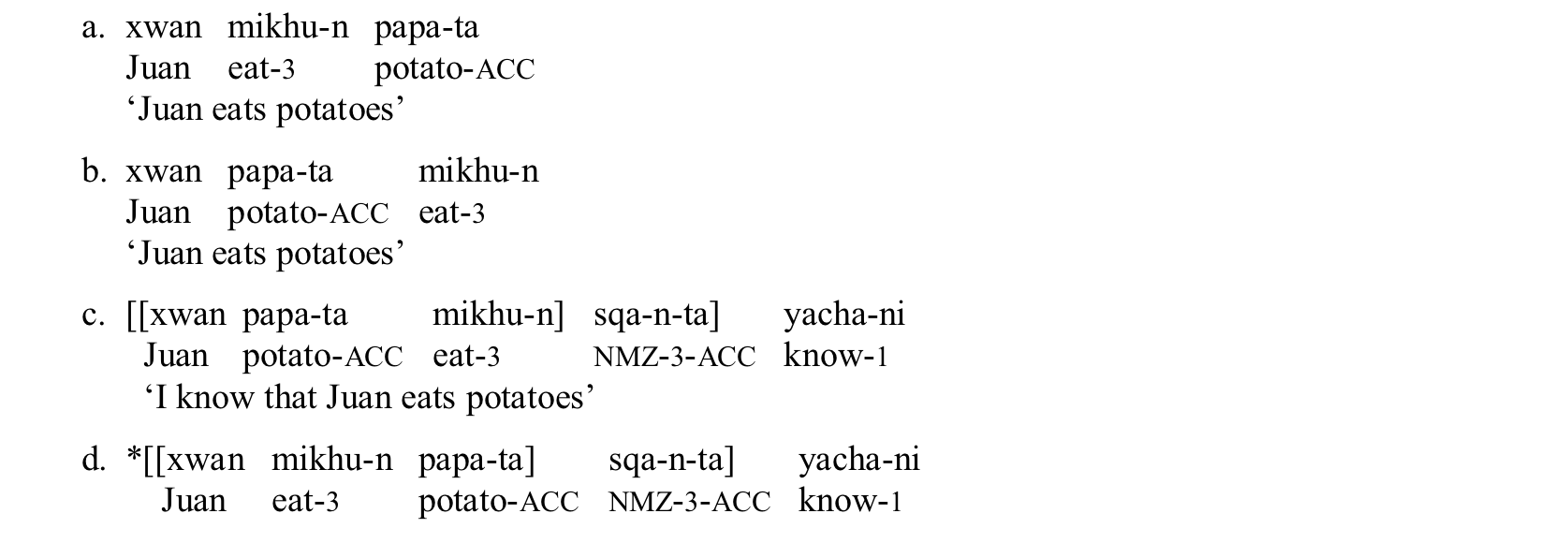

Another example of an ACCESS violation in which syntax/semantics ‘sees’ morphology is provided in Example 11. As discussed by Ackema and Neeleman (2004:11)20, the order of the verb with respect to its object NP in Quechua is relatively free – the verb can precede the object NP, as in 11a, or follow it, as in 11b. However, if the VP is nominalized (denoted by the presence of the nominalizer sqa), only the object-verb pattern is permitted (cf. the grammatical acceptability of 11c with that of 11d). Therefore, these cases are representative of an ACCESS violation where syntactic ordering is dependent on the presence of specific morphological forms (i.e., syntax apparently accesses morphology in order to determine word order)21.

Example 11

Certain varieties of Dutch provide justification for a second subtype to ACCESS violations. In contrast to examples where syntax appears to be conditioned by particular morphological forms, Ackema and Neeleman (2004:11) observe that in East Netherlandic varieties of Dutch22, one inflectional paradigm is used if the verb follows the subject NP (as evidenced by the -t plural marker in Example 12a), and another paradigm is used if the verb precedes its subject (the -e plural marker in 12b). Examples such as these (as well as instances of construction-dependent morphology as discussed by Booij (2005)), support the possible ACCESS subtype ‘morphology sees syntax/semantics’.

Example 12

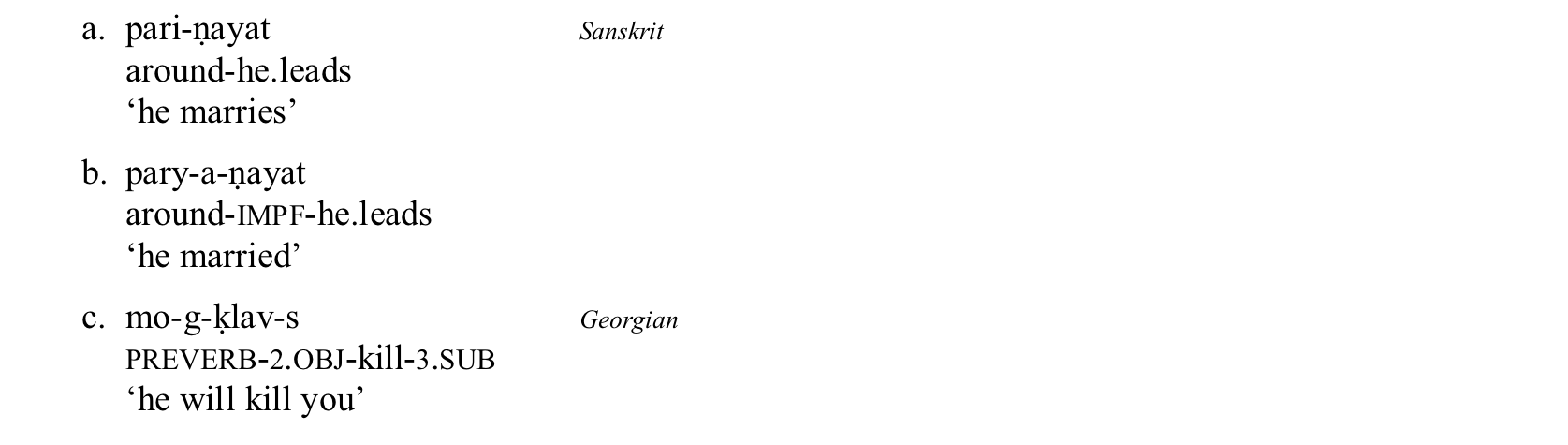

Finally, violations may manifest as a matter of unpredicted linguistic forms in relation to the sequential order of grammatical components (namely, word formation preceding syntax) assumed by LI. Example 1323 provides instances of ORDER violations on the word-level; the Sanskrit example in 13a demonstrates the derivational function of the preverb pari-, which, together with the lexicalized verb root ṇayat ‘he leads’, produces the composite verb form pariṇayat ‘he leads’, while the inflected form in 13b exhibits the temporal prefix a- between the derivational preverb pary- and the root/stem. This morphemic order of DERIVATION-INFLECTION-ROOT/STEM violates prediction (3) made by LI of a strict INFLECTION-DERIVATION-ROOT morpheme order (in the case of prefixation in 13b, and ROOT-DERIVATION-INFLECTION with respect to suffixation). The Georgian verb in 13c demonstrates a similar (unpredicted) morphemic order of DERIVATION-INFLECTION-ROOT/STEM-INFLECTION.

Example 13

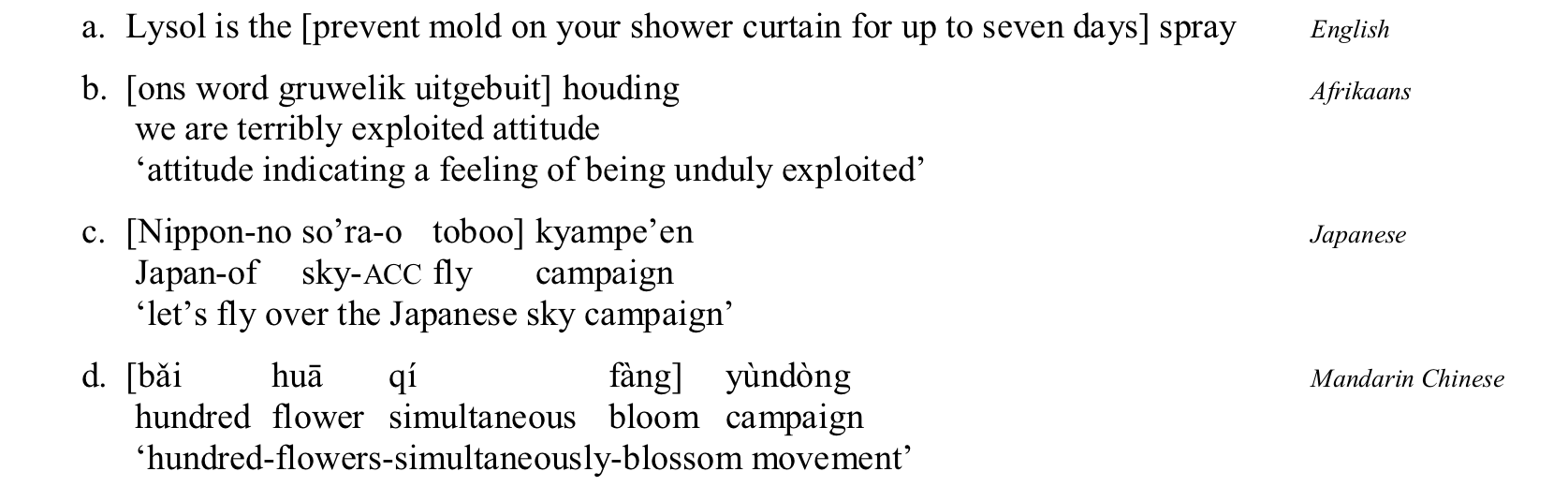

ORDER violations may also appear on the phrase-level, as in cases of phrasal derivation (e.g. Example 4, Section 1.2) and phrasal compounding24 where syntax appears to function as the input to word formation. For example, Bruening (2018:4) provides the American English advertisement in Example 14a, in which a full VP functions as an adjectival modifier within the NP NP[the VP[prevent-mold-on-your-shower-curtain-for-up-to-seven-days] N[spray]]. Botha (1981:76), Tokizaki (2017:2), and Wiese (1996:185) provide similar examples in Afrikaans, Japanese, and Mandarin Chinese, respectively25.

Example 14

Up to this point, the term ‘word’ has been used in reference to morphology, syntax, their interface, and various LI violations. Considering the lack of any clear definition or understanding of the notion ‘word’ (Haspelmath 2011), and given the present goals of this paper, no attempt at defining it will be made. Rather, following Sag (2012:97-98), ‘word’ will be considered a cover term based on a given linguistic expression’s (i.e. sign, in the sense of de Saussure (1983)) privilege of instantiation as a daughter node in a phrasal construction26.

Section 2 Footnotes

14: In several cases a direct relation between challenges to LI cannot be determined, largely due to theoretical disagreements on what constitutes a morphological and/or syntactic process, how strongly or weakly lexicalist one’s assumptions are, whether semantics is considered separately from morphology and syntax, how fine-grained one chooses to be when distinguishing individual challenges to LI, etc. For example, Lieber and Scalise’s (2007) category (a) (morphology has access to syntax) subsumes phenomena which Booij (2005, 2009) treats as belonging to both ‘accessibility’ and ‘manipulation’ violations, while Booij’s ‘accessibility’ and ‘manipulation’ is silent on the ordering relationship noted by Bruening (2018) (Error 1, which is itself related to Lieber and Scalise’s category (a)). This should serve to illustrate the tenuous nature of both LI and the precise linguistic phenomena it is intended to prevent.

15: Interestingly, this theoretical prediction is at least somewhat typologically supported by Greenberg’s (1963) observation that derivational morphemes tend to appear closer to the root than inflectional affixes (Booij 2009:1).

16: The full taxonomy of LI violations, which provides additional detail regarding individual languages, their specific violation types, and their scholarly sources, is omitted from the present discussion due to size and formatting constraints. However, the full taxonomy is provided in Appendix 7.2.

17: † marks situations in which a syntactic MANIPULATION (word-part ellipsis) violation can be morphologically analyzed in terms of a syntactic/semantic ACCESS violation of word-internal structure. ‡ indicates that specific phenomena constituting apparent phrase-level ORDER violations (e.g. bracketing paradoxes) may be recharacterized as particular forms of ACCESS violations. Finally, § represents the fact that both ACCESS subtypes (syntax/semantics ‘sees’ morphology, and morphology ‘sees’ syntax/semantics) could possibly be collapsed into a single ACCESS violation, as opposed to specifying the directionality of the alleged access. For all intents and purposes, each potential violation type and subtype is kept distinct; however, future work will ideally explore the nature of these violation types (and subtypes) in more detail.

18: If certain weakly lexicalist approaches are adopted, this would not theoretically constitute a violation, since it is stipulated (e.g. in Aronoff’s (1976:8-9) formulation of the (weak) lexicalist hypothesis) that syntax deals with other situations of movement of morphemes, such as affix hopping and clitic rules.

19: Language data examples original to: Spencer (2005:82) (English); Booij (2009:88), Vigario (2003:251) (Portuguese); Akkuş (2015:2-3), Lewis (1967:35) (Turkish).

20: Originally noted by Lefebve and Muysken (1988:18).

21: In connection with the note on potential points of reanalysis in f.n. 17 (this section), the data in Example 11 could also be viewed as an instance ‘morphology sees syntax’, with morphology accessing the word order of the phrase to which it attaches, as opposed to the ‘syntax sees morphology’ analysis provided by Ackema and Neeleman (2004). Of course, there could be an entirely morphological explanation as well, where the nominalizer can only attach to a lexical verb.

22: Originally noted by van Haeringen (1958).

23: Language data examples original to Beard (1998:45-46).

24: Phrasal compounding has been formally characterized by Meibauer (2007:234) as a word formation process “of the type YP+X, with YP modifying X semantically”, e.g. [VP[prevent mold on your shower curtain …] + N[spray]].

25: Phrasal compounding is quite common cross-linguistically, and has been discussed in relation to English (e.g., Bauer 1983, Lieber 1992, Carney 2000, Lieber and Scalise 2007, Bruening 2018, among many others); Afrikaans (e.g., Botha 1981, Savini 1983); Dutch (Ackema and Neeleman 2004); Swedish (Mukai 2006); German (Meibauer 2007); Japanese (Tokizaki 2017); Mandarin Chinese (Wiese 1996, Tokizaki and Kuwana 2008); French and Danish (Bauer 1983). Furthermore, phrasal compounding appears to be highly productive within and across languages, as noted by Bauer (1983), Ackema and Neeleman (2004), Meibauer (2007), Trips (2012), and Tokizaki (2017) (citing Kubozono (1995)). Observations such as these contradict Bresnan and Mchombo’s (1995) and Wiese’s (1996) attempts to characterize phrasal compounding as a result of lexicalization or quotation; it is not clear how a productive (and in many cases novel, as e.g. demonstrated by Trips (2012)) use of a phrasal compound becomes instantly lexicalized for the purposes of the morphology-syntax interface.

26: This more general conceptualization of ‘word’ is contra Booij (2009), who uses LI and word-cohesiveness in order to define the notion of wordhood, stating “I consider the impossibility of syntactic movement of the constituents of a linguistic unit as a necessary condition for that linguistic unit to be a word” (pp. 85), and in particular regard to LI “[the prohibition on movement] part of [LI] may serve as a basic test to find out if a sequence of morphemes is a word or a phrasal lexical unit” (pp. 86). However, Haspelmath (2011:25) cautions against this very approach to defining wordhood: “The really serious problem resulting from the indeterminacy of word segmentation is that linguists often presuppose the word concept and the morphology-syntax division, and even try to use it for explanatory purposes. Some of the contexts in which the word as a cross-linguistic category and/or the syntax/morphology division is presupposed [include] the Lexical Integrity Hypothesis (e.g. Bresnan and Mchombo 1995)”.